If you enjoyed these Service Reflections, please forward to other Veterans who may be interested. | |

|

|

|

|

OF A Navy VETERAN

Aug 2020

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tritten, James CDR

|

|

| Status |

Service Years |

|

|

|

USN Retired

|

1965 - 1989

|

|

|

| NEC |

|

|

131X-Unrestricted Line Officer - Pilot

|

|

|

| Primary Unit |

|

|

1986-1989, 131X, Naval Postgraduate School (Faculty Staff)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Record Your own Service Memories

By Completing Your Reflections!

|

|

|

Service Reflections is an easy-to-complete self-interview, located on your TWS Profile Page, which enables you to remember key people and events from your military service and the impact they made on your life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

Please describe who or what influenced your decision to join the Navy.

|

| |

|

| My Enlistment |

My father served in the U.S. Navy as an aviation metalsmith. He joined before America went to war and served a bit after World War II. He was very proud of his service and having made 1st Class Petty Officer. He flew a bit on non-crew skins and arranged for me to go for a ride in a seaplane, perhaps even the SOC-1 he worked on, on the Hudson River when I was a kid. I was bitten by the aviation bug from that point on and also by the U.S. Navy.

After high school, I went off to college but kept visiting the local recruiter in my home town. I took tests, talked to him, and was surprised when he told me not to enlist but to stay in school and come in an officer after I graduated.

Money was tight, I was burned out from working full-time and going to school full-time. My grades suffered to the point that I questioned whether the effort was worth it. So, in the spring of 1965, I researched what type of programs I could qualify for leading to an aviation career. The Navy at the time still had officer programs for individuals without a college degree. I learned I needed one more class to qualify and needed a grade of C in that class to get off probation. I took a summer class, earned a C, and was sworn into the Navy in September, and reported to Pensacola in October 1965.

|

| |

|

Whether you were in the service for several years or as a career, please describe the direction or path you took. What was your reason for leaving?

|

| |

|

| 1970 promotion to LT and augmentation to USN |

I completed my first tour of active duty as a reserve officer. In September 1969, the Navy offered those of us who had been commissioned under the Naval Aviation Cadet program, the opportunity to be released to inactive duty before the end of our contract. I took the option and affiliated with the Naval Air Reserves as a pilot for thirteen months. I also went back to the university to finish up my undergraduate degree and flew in the reserves on the weekends. After serving as a reservist and undergraduate student, I decided to return to the Navy on active duty.

So here is the interesting thing. I had never been a regular officer. But I learned that there was (in 1969) a provision for reservists (USNR-R) to apply for augmentation to become a regular officer. So, I applied. But I wrote in the application that I would not accept the commission unless I were allowed to stay in school and finish my senior year. I had gotten the message earlier that an officer without a college degree had no future on active duty.

To make it easier for the augmentation board, I also applied for the College Degree Completion program, known generally as the BS/BA program. An interesting thing about that is that nowhere in the directives did it say you actually had to be on active duty in the Navy to apply. So I did. And I wrote in the application that I could not accept it unless I was brought back on active duty. And I would not take the orders unless I was simultaneously augmented into the regular Navy.

I was accepted for both.

Then the problem was at what rank. I had gotten off active duty a few weeks before the active duty LT board met. So, I was still a reserve LTJG. The reserve LT board met, and I was selected. But the paperwork was not done yet. So, I walked my promotion paperwork through the Bureau of Naval Personnel so that I could be promoted to LT in the reserves, then augmented as an LT to the regular Navy, and then accepted orders to stay in school and finish my undergraduate education. All done on the same day if I recall.

I finished my education and was given orders back into the fleet as a carrier pilot. I remained on active duty until 1989 when I retired.

|

| |

|

If you participated in any military operations, including combat, humanitarian and peacekeeping operations, please describe those which made a lasting impact on you and, if life-changing, in what way?

|

| |

|

| Norwegian Sea Crash 1968, Article |

After I received my wings, I went through antisubmarine warfare training at NAS Norfolk, Virginia, and in the Replacement Air Group (RAG) squadron Air Antisubmarine Squadron THIRTY at NAS Key West Florida. After completing the RAG, I was told my ultimate duty station squadron had ordered me to attend Nuclear, Biological, & Chemical Warfare School at the Army's Fort McClellan, Alabama. Little did I know the impact that a two-month diversion would have.

I reported to Air Antisubmarine Squadron THIRTY-FOUR (VS-34) at NAS Quonset Point Rhode Island at the end of the year, 1967. All of the other new pilots had arrived right after the RAG, and I missed getting worked up for deployment. My first cruise was aboard USS Essex (CVS-9) in early 1968. I was a newly reported fleet Ensign. We went to both the Mediterranean and northern Europe, like a nugget who had not been worked up with the rest of the squadron, Assigned as co-pilot with, the commanding officer. I rode the right seat of the S-2E the entire cruise. I got promoted to LTJG as a reserve officer. I was pretty dejected by watching my other shipmate's bag traps from time to time. Needless to say, not only did this sour me on the Navy, but it also impacted what would happen next.

After Essex and VS-34 returned from the cruise, we did some shore flying that included patrols out of NAS Key West, Florida, where we spent hours in the Bermuda Triangle looking at shipping coming to and from Cuba. Shortly after that, the squadron was told the ship, the air wing, and the squadron was being decommissioned. I was hand-picked to join our executive officer in another VS squadron. By this time, I had had it with the VS community. My peers had all made the first rung at working their way up to be aircraft commander, and I was still stuck as a new guy, mostly in the right seat.

When a large number of units decommissioned, the detailers came to us rather than having to make a phone call or go to the Bureau of Naval Personnel in Arlington, Virginia. I asked the detailer if I could get different orders. He said his hands were tied because the XO had asked for me. I then said to him, one of the other pilots had been given orders to Tactical Electronic Warfare Squadron  THIRTY-THREE (VAQ-33), also at Quonset Point, and he did not want the orders. The detailer asked me if, as a reserve officer, I was going to stay in the Navy. I asked him how I should answer that. He said the other officer is a regular and wants to stay in the Navy. If you intend to remain a reservist and get out after your obligated service, then he would swap the orders. I told him I did not intend to stay in the Navy. THIRTY-THREE (VAQ-33), also at Quonset Point, and he did not want the orders. The detailer asked me if, as a reserve officer, I was going to stay in the Navy. I asked him how I should answer that. He said the other officer is a regular and wants to stay in the Navy. If you intend to remain a reservist and get out after your obligated service, then he would swap the orders. I told him I did not intend to stay in the Navy.

Flying the EA-1F, the A-1E, and the EC-1A as a member of VAQ-33 was terrific. I was the only pilot in a single-engine airplane. I got carrier qualified day and night aboard Essex and again later aboard USS Lexington (CVT-16). Since I had just returned from a cruise, the skipper let me off of the next detachment, and I prepared to go to sea in the fall of 1968. As luck would have it, the unit was transferred to NAS Norfolk, with only the CO/XO and Command Master Chief if I recall correctly. Our aircraft were all sent to the boneyard and the entire complement of personnel given orders elsewhere. VAQ-33 was my best experience flying. I even made aircraft commander in the EC-1A and took lots of my VS friends up on rides in the A-1E.

My transfer was to Transport Squadron THIRTY (VR-30) at NAS Alameda, California. This "tour" would only last a few months. I got carrier qualified and bagged traps in the C-1A. One day, I went into work and told the CO & XO wanted to see me. I thought, what have I done wrong now? Instead, they painstakingly explained there was a new program of early outs where reserve officers were being released to inactive duty. They told me they wanted me to stay in the squadron and were sure they could arrange for my name to be taken off the list. I asked when I could be released. They scratched their heads and decided that I could go anytime I wanted. I told them I had the duty the next day, and I would like to get out instead. I did and was drilling with a reserve VS squadron also out of Alameda that weekend.

I went back to university as a reserve officer and drilled on the weekends at NAF Washington, DC (located aboard Andrews AFB, Maryland). I flew the S-2E and the SP-2H. After completing college, I was a regular officer and had been promoted to LT. Assigned to a fleet VS squadron out of Quonset Point and again went through the RAG and then to Aviation Safety Officer School at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California.

When I reported for duty to VS-27 at the end of 1971, I was the senior LT and the Aviation Safety Officer. We flew the S-2E, and I qualified as an aircraft commander. We deployed aboard USS Intrepid (CVS-11)  to the North Atlantic and flew in an Ocean Safari exercise in the Norwegian sea. We came home from that cruise early, were given S-2Gs to fly, and immediately deployed again this time for the Mediterranean. We returned from being at sea for over a year. Right after we returned, the ship, air wing, and squadron were all decommissioned. I asked for a shore flying assignment and was sent to Training Squadron THIRTY-ONE (VT-31) out of NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, where I instructed in every phase of advanced flight training to include taking students to the boat for the first time, and I got to bag more traps. By March 1975, I was done and ready to go back to sea. to the North Atlantic and flew in an Ocean Safari exercise in the Norwegian sea. We came home from that cruise early, were given S-2Gs to fly, and immediately deployed again this time for the Mediterranean. We returned from being at sea for over a year. Right after we returned, the ship, air wing, and squadron were all decommissioned. I asked for a shore flying assignment and was sent to Training Squadron THIRTY-ONE (VT-31) out of NAS Corpus Christi, Texas, where I instructed in every phase of advanced flight training to include taking students to the boat for the first time, and I got to bag more traps. By March 1975, I was done and ready to go back to sea.

I had a ship's company tour aboard USS Independence (CV-62) out of NS Norfolk. We deployed to Europe twice, and I flew the ship's C-1A as aircraft commander from 1975-1977. My first flight was my NATOPS check. I got lots of traps because there were very few pilots as ship's company that had time in the S-2 or C-1. My shipboard assignment was in the antisubmarine warfare module of the Combat Information Center. Good flying and a good ship's job. We broke in the new computerized ASW module that supported the S-3A.

My final fleet squadron was VS-22 out of NAS Cecil Field, Florida, and aboard USS Saratoga (CV-60). I flew the S-3A as an aircraft commander, and we deployed twice to the Mediterranean. Jets are faster and can cover more distance, but frankly, I did better ASW in the S-2G and my best flying in the S-1. When I left the squadron, I left the fleet and never returned. We had one hell of a farewell at the NAS Jacksonville Florida Officers Club.

|

| |

|

Did you encounter any situation during your military service when you believed there was a possibility you might not survive? If so, please describe what happened and what was the outcome.

|

| |

|

| LCDR Jim Tritten by an S-3A |

Yes, I was riding in the right seat of an S-3A one night in 1979 when the aircraft struck treetops and the ground during an abortive landing. I have subsequently been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a result of this aircraft accident.

|

| |

|

Of all your duty stations or assignments, which one do you have fondest memories of and why? Which was your least favorite?

|

| |

|

| VAQ-33 A-1E Buno 135188 |

VS-27 out of NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island, and deployed aboard USS Intrepid (CV-11) was simply the best unit ever. We flew the S-2E and S-2G. The latter was the last version of the Stoof to be delivered to the Navy. Our squadron won every possible trophy and award.

VS-27 out of NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island, and deployed aboard USS Intrepid (CV-11) was simply the best unit ever. We flew the S-2E and S-2G. The latter was the last version of the Stoof to be delivered to the Navy. Our squadron won every possible trophy and award. But that is not what set it apart.

First, command leadership was exceptional. I served under two of the finest Commanding Officers ever. They embodied how to run a military unit. They trusted their subordinates and gave them latitude to try and fail without being punished. The Zumwalt-era relaxations contributed. Officers were allowed to serve in billets generally reserved for one grade more senior. I served as a department head as the senior LT. I was the Senior Watch Officer, an aircraft commander, and even rated a two-person stateroom.

VS-27 was a professional success at the same time as the officers had fun. We partied like there was no tomorrow when we pulled into port. All the junior officers got along and proved the old adage about working hard and playing hard. My guess is some of the things we did would not be condoned today. But our group of officers has stuck together throughout the years and had numerous enjoyable reunions.

Of interest is that we did all this when personal awards were simply not given to anyone who was not in combat. We did our jobs, did them well, and walked away from the best squadron in the Navy with the inner satisfaction we had done well.

VAQ-33, also out of Quonset, was where I enjoyed flying the most. Nothing like being the only pilot in a single-engine aircraft. There was no better bird for me in my entire career. Of course, flying an old prop in the last operational squadron to fly the A-1 was a total career mistake. But one I would do over again in a heartbeat.

Other units were good, and I have fond memories of each. But nothing compared to the two above.

|

| |

|

From your entire military service, describe any memories you still reflect back on to this day.

|

| |

|

| The JORP Lives |

Anyone who has been in the U.S. Navy, or any of the military services, has had the occasion to gripe about the system, those senior to them, their current duty station, or just life in general. Venting about the injustices of life is pretty normal and can lead to unintended consequences. In the late 1960s, one wardroom of junior officers (JOs) assigned to Air Antisubmarine Squadron TWENTY-SEVEN (VS-27), created a formal mechanism to capture these types of happenings in an official U.S. Navy logbook. The green ones that we would punch a hole in the cover and stick in a pen.

The Junior Officer Retention Program (JORP) was conceived, organized, and managed by those officers in the squadron above the rank of Chief Warrant Officer and below the rank of Lieutenant Commander. At their request, the JORP did not include Limited Duty Officers. VS-27 had Canadian Navy exchange pilots. They were not included. In other words, the JORP embraced all U.S. Navy junior officers with the ranks of Ensign, Lieutenant Junior Grade, and Lieutenant. All were naval aviators except for the squadron intelligence officer and one naval flight officer.

Instead of hunkering down and mindlessly suffering at the hands of the "heavies," or the system at large, the JOs would get the JORP log from the senior Lieutenant, and on their own, with no adult supervision, document what happened and who the perpetrator was. It was a great way to blow off steam.

The first entry in the JORP log was:

"JORP (Jr. Officer Retention Program) Dedicated to the fallacies of 'Heavies' ideas of building the exuberance of 'JO's' desire to continue their careers in the 'program.'" Now you may notice that the above dedication makes no sense and is not written in English. After polling the group in preparation for this essay, one of our JOs replied: "Since when was something that made no sense ever a problem for this august group?" Clearly, there was some alcohol involved with the writing of the dedication.

Typical entries in the JORP log included [re-written into proper English]:

1. Last night, one of our heavies needed one more successful night illumination of the target ship to get his crew a searchlight qualification. The circuit breaker kept popping, so this heavy pushed it back and held it in. The searchlight overheated melting the housing, mirror, and Plexiglas dome. He did get the qual even if he endangered the lives of his crew, and the safety of the airplane. 1. Last night, one of our heavies needed one more successful night illumination of the target ship to get his crew a searchlight qualification. The circuit breaker kept popping, so this heavy pushed it back and held it in. The searchlight overheated melting the housing, mirror, and Plexiglas dome. He did get the qual even if he endangered the lives of his crew, and the safety of the airplane.

2. One of the heavies got so carried away chewing out a JO in flight that no one was flying the aircraft. When the radar altimeter alarm went off at 100 feet, they got back to aviating.

3. An analysis of the flight schedule revealed that JOs were assigned most of the night flights while the heavies flew only in the daylight under clear blue skies, calm seas, and a steady deck.

4. One of our JOs and his crew in one aircraft and a heavy with his crew in another aircraft were working a submarine, initially detected by the crew in the JOs aircraft. At the debrief, the heavy took credit for finding the contact leaving the JO and his crew open-mouthed.

5. One night, after launching six aircraft, the ship changed its intended direction over the next six hours (PIM) by 180 degrees (in the opposite direction than originally briefed) with an increase in speed by a factor of two without transmitting the change to the aircraft what was airborne. Guess where we all went to meet the ship for recovery. Guess where the ship was (not). Their excuse? We went into EMCON (radio silence) after the launch. The JO's were not amused, and the ship had to break EMCON anyway to get us back aboard.

6. Following a personnel inspection in port overseas, the Skipper dismissed the enlisted men and held close order drill on the flight deck for all officers. You have never seen such a bedraggled group of hung-over Navy officers trying not to fall over their feet. The warrants, limited duty officers, and Canadian exchange officers got caught up with this one.

7. One of the heavies begged to be admitted into Papa Z's, the junior officer club, at NAS Quonset Point, Rhode Island. It was embarrassing for everyone to see him grovel, so we finally let him in. There was a dancer worth seeing that evening, and he contributed more money than anyone else ? only fitting since he was senior and made more money.

8. After a change of command, the JOs found a box of the former Skipper's calling cards. They passed out at every cat house in the Mediterranean. Heh, heh, heh. JO's getting revenge even after the fact.

The worst heavies were the Lieutenant Commanders (LCDR's), the next pay grade above that of Lieutenant, and just below the rank of Commander. Keeping the JORP log out of their hands became a game that was played by all. And of course, the JOs would torment the LCDR department heads by telling them we were going to write something into the book about them and never show them what was written. They tried to steal the log making the job of the senior Lieutenant, and logbook keeper, interesting at times. As the current senior Lieutenant and keeper of the log rotated to his next duty station, there was a "change of command" a ceremony, of sorts, with the JORP log being passed to the new senior Lieutenant. The worst heavies were the Lieutenant Commanders (LCDR's), the next pay grade above that of Lieutenant, and just below the rank of Commander. Keeping the JORP log out of their hands became a game that was played by all. And of course, the JOs would torment the LCDR department heads by telling them we were going to write something into the book about them and never show them what was written. They tried to steal the log making the job of the senior Lieutenant, and logbook keeper, interesting at times. As the current senior Lieutenant and keeper of the log rotated to his next duty station, there was a "change of command" a ceremony, of sorts, with the JORP log being passed to the new senior Lieutenant.

One of the more humorous methods to pay back the heavies was in the use of the black spot. You know the same black spot that Blind Pew gave Billy Bones and George Merry, Tom Morgan, and Dick Johnson gave to Long John Silver. For those of you who can't remember, that was in Treasure Island. Black spots mysteriously appeared rolled up in the wardroom napkins or inserted into personally addressed envelopes in the miscreants' mailbox.

There was one heavy, known affectionately as "The Rabbit" (or "Cwaze" for crazy Rabbit) who would twitch and flap his arms upon receipt of the black spot or the release of a mechanical rabbit in the ready room whenever he got up to speak. We were mean, but what do you expect from JO's. At the Rabbit's farewell, one of the JOs rented and appeared in a rabbit suit. Before the evening was over, everyone ended up in the swimming pool, including the Cwaze.

Once the heavies learned about the JORP log, they took steps to find out what was recorded and said about them. That is, all the heavies but the commanding officer (CO) and his exec (XO) who were full Commanders. They understood what was going on and that it was healthy for unit morale. Never-the-less, they never got to see the JORP log even if we would have followed our skippers anywhere. It was a very interesting situation with the two senior officers of the squadron giving tacit approval to the activities of the JORP. At the same time, the LCDR department heads, one in particular, were apoplectic about our activities.

When the squadron decommissioned in 1973, the logbook was probably given to someone to keep for posterity. No one remembers, we were only irresponsible Junior Officers, right? But the legacy of the JORP was far from over.  Many years later, when one of our squadron JOs ran into someone stationed with The Rabbit, the JO quickly crafted a black spot with the words "The JORP is watching" on the back. He asked that the black spot to be left on the desk or office mailbox of the poor Crazy Rabbit. Similar reminders were sent in the mail as we learned of former VS-27 heavies posted at new commands. Many years later, when one of our squadron JOs ran into someone stationed with The Rabbit, the JO quickly crafted a black spot with the words "The JORP is watching" on the back. He asked that the black spot to be left on the desk or office mailbox of the poor Crazy Rabbit. Similar reminders were sent in the mail as we learned of former VS-27 heavies posted at new commands.

Thirty years later, when we all met again at a Reno reunion, the JORP log was a major topic of conversation. The heavies asked if they could finally see the book. The JOs all pointed fingers at each other and said that the other fellow had it. The solution? Re-create the JORP log with embellished stories that we could all recall. VS-27 JO's might have been somewhat irresponsible in the day, but we were crafty and mean.

At each reunion, more and more of the stories were remembered and entered into a new JORP log based upon the original. This effort included keeping prying heavy eyes off the hallowed pages of truth, as only experienced by a junior officer in the U.S. Navy at the time.

In addition, each of the heavies who had been targeted by a JORP black spot in their later careers fessed up to having received the warning. They all asked how on earth the JO's had managed to deliver a black spot to them so many years later. At one reunion, when the Cwaze finally recognized one of the JO ringleaders, he squinted and said, "You were a real thorn in my side." We asked him if he got the black spot when he stationed elsewhere. He began to twitch, his shoulders shuddered, hands shook, and lips danced up and down as he melted in front of us into an approximation of Elmer Fudd facing that irascible Bugs Bunny.

At least one of the JORP log stories was converted, from the pilot talk in the logbook into a short story that could be read and appreciated by anyone. This one-story involved the back and forth decision-making in the cockpit of an S-2G, which lost an engine a few hundred miles from the nearest land airfield in Norway. At night. In storms. _underway_c1964.jpg) With an extremely pitching deck on USS Intrepid (CVS-11). The story can be accessed at http://theaviationist.com/2015/01/23/s-2-flying-to-norway/ and should give any reader an appreciation not only of flying from an aircraft carrier, an in-flight emergency but more importantly the dynamics between a senior officer and a junior officer when the chips were really down. If you want to read a fully developed essence of the JORP, read this story. With an extremely pitching deck on USS Intrepid (CVS-11). The story can be accessed at http://theaviationist.com/2015/01/23/s-2-flying-to-norway/ and should give any reader an appreciation not only of flying from an aircraft carrier, an in-flight emergency but more importantly the dynamics between a senior officer and a junior officer when the chips were really down. If you want to read a fully developed essence of the JORP, read this story.

At some point, after VS-27 started having regular reunions, we heard about the Junior Officer Protection Association (JOPA). The JOPA Facebook page defines JOPA as:

"The bottom three grades of Navy/Marine Corps Officers band together to take care of each other against the backdrop of senior officers (specifically fleet-level O-4s and O-5s) who are less concerned with them than they are advancing their careers." It sounds exactly like the VS-27 JORP! Except for the Marines part. I mean, we didn't even let in our Canadians.

At a 2018 reunion of VS-27 officers in Pensacola, one of our former JOs met with two currently active-duty naval aviators and learned that JOPA is well-known throughout the fleet and not restricted to pilots. Those of us at the reunion decided that we would document the JORP, make that history available to the National Naval Aviation Museum, and donate the re-created JORP log to the collection. We made a visit to the museum staff where it was agreed that we would donate the JORP log and an essay (this document) that described the JORP and highlighted its similarity to JOPA.

At this 2018 reunion, one of the former VS-27 skippers brought out a beat-up green logbook with half of the pages ripped out. On the first page, after the deleted section, were the signatures of the JOs from VS-27 at the time of his change of command in 1972.

Did the heavies manage to get their hands on the JORP log after all? Did they rip out all of the entries painstakingly made all those many decades ago? All other former squadron heavies denied any knowledge of the book or having ever glimpsed the pages of the holy JORP log. Fortunately, the Skipper admitted it was given to him at his change of command as a farewell gift from the JOs.

.jpg) Next, one of the heavies tried to convince everyone that the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) had an official U.S. Navy Junior Officer Retention Program at the time. One of the former skippers, who had worked in the officer retention area at BUPERS, said there never was any official JORP mandated by the Navy. He acknowledged the JORP was homegrown by disgruntled brig rats in the squadron. We'll trust the Skipper's memory on this one even if it does not appear that any of our shenanigans ever landed any of the JOs in the brig. Maybe in the hack, but never the brig. Next, one of the heavies tried to convince everyone that the Bureau of Naval Personnel (BUPERS) had an official U.S. Navy Junior Officer Retention Program at the time. One of the former skippers, who had worked in the officer retention area at BUPERS, said there never was any official JORP mandated by the Navy. He acknowledged the JORP was homegrown by disgruntled brig rats in the squadron. We'll trust the Skipper's memory on this one even if it does not appear that any of our shenanigans ever landed any of the JOs in the brig. Maybe in the hack, but never the brig.

And just in case anyone reading this wonders if we had time to do our jobs, VS-27 was the most recognized air antisubmarine squadron on the east coast at the time. Our unofficial motto was to work hard and play hard. The JORP was part of both. It allowed us to record, discuss, and then contemplate the actions taken by the heavies in getting the many official awards bestowed on the squadron. And to think about how we would handle the same situations when we had been promoted out of the JO ranks, and ourselves became heavies.

So, for those of you, Junior Officers, and members of JOPA, we who have gone before you wish you the best in your efforts to tell it like it is. The tension between JOs and the heavies is inevitable. And nothing to fear. There was never any chance that JORP activities would result in a mutiny. Just a lot of good stories to be told, and re-told over the years, and now documented for you to read about in the museums archives. And maybe because they knew the JORP was watching them, maybe we saved a life or two. And we had fun.

|

| |

|

What professional achievements are you most proud of from your military career?

|

| |

|

| Winging April 27, 1967 |

Earning my wings as a naval aviator in April 1967. Getting my wings came a day or two after I was commissioned as an Ensign having now finished flight training.

As a Naval Aviation Cadet, I went through flight training as an enlisted man. The day after I flew my last flight, I went over to student administration at NAS Corpus Christi, signed some papers, and then some crusty looking LCDR looked up at me and told me I was out of uniform. I went into the head and took off my cadet insignia and pinned on my bars as an Ensign, USNR. Some commissioning.

The weekly winging ceremonies in Corpus Christi were usually low-key affairs done in front of the admiral's headquarters. I told my mother not to bother coming. That day, they bussed us out to the parade field where the bleachers were filled with spectators. A Marine Corps band had was brought in from Washington, DC. We did not know that. We all lined up, and the band played and marched. It was an incredible ceremony right out of Hollywood World War II movies. I never told my mother what she missed.

Getting my wings is the foundation of everything that happened to me since that date. I still wear shirts embossed with the wings of gold. There is no other professional achievement that I am more proud to include earning two Master's degrees and a Ph.D.

|

| |

|

Of all the medals, awards, formal presentations and qualification badges you received, or other memorabilia, which one is the most meaningful to you and why?

|

| |

|

| Andrew Marshall, Director Net Assessment, pinning on the DSSM |

My being presented the Defense Superior Service Medal (DSSM) in 1986 by Mr. Andrew Marshall, Director Net Assessment, in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. That tour of duty as Assistant Director was absolutely an incredible experience for me right out of my Ph.D. at the University of Southern California.

It was being presented the Defense Superior Service Medal (DSSM) in 1986 by Mr. Andrew Marshall, Director Net Assessment, in the Office of the Secretary of Defense. That tour of duty as Assistant Director was absolutely an incredible experience for me right out of my Ph.D. at the University of Southern California. I did things working there that molded the next phases of my career.

I interacted with the Pentagon establishment and learned how the Department of Defense really worked. I applied the knowledge from both the fleet and my formal education to represent the Navy well in OSD. I also saved the Navy from having things done to them that was not seen from the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. I was proud of my work is OSD, and being awarded the professional recognition I received.

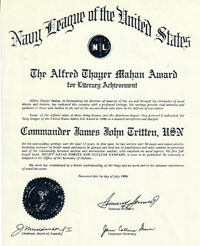

Andy nominated me, and I was awarded the Navy League of the United States Alfred Thayer Mahan Award for Literary Achievement in 1986. There have been very few active-duty officers to have ever won this award, and I am extremely proud of having been so recognized.

|

| |

|

Which individual(s) from your time in the military stand out as having the most positive impact on you and why?

|

| |

|

| Safety pays off article |

The leadership of VS-27 aboard USS Intrepid (CVS-11) being presented the Aviation Safety Award for three years of accident-free flying. The article also mentions we won the CAPT Arnold J. Isbell Trophy as well as the Battle “E.”

|

| |

|

List the names of old friends you served with, at which locations, and recount what you remember most about them. Indicate those you are already in touch with and those you would like to make contact with.

|

| |

|

| VS-27 Reunion |

Too many to list. I regularly participate in reunions associated with VS-27 and all aviators that flew any variant of the S-2.

|

| |

|

Can you recount a particular incident from your service, which may or may not have been funny at the time, but still makes you laugh?

|

| |

|

| USS Independence COD |

During the Winter of 1976-1977, I contracted pneumonia and hospitalized at the Naval Hospital in Portsmouth, Virginia. My ship, USS Independence (CV-62), went to the Caribbean while I convalesced in Virginia. Once the NAS Norfolk flight surgeon gave me an "up chit," I flew down to NAS Roosevelt Roads, Puerto Rico on a transport, and was then a passenger in one of two C-1A CODs going out to Indy. When I got on the ship, my boss, the Operations Officer, called me to his office. He told me I had been skating ashore for the past month while they were working, and ordered me to man up the ship's COD immediately and fly ashore and return with passengers and cargo ASAP.

So, I changed into my flight suit and went up on the flight deck and manned up C-1A 136790 with a full load of passengers. The two other C-1As and I started our engines. The flight deck crew taxied all three of us down the angle deck. I was number three in line as we taxied aft. When we got as far back as we could, the flight deck crew turned us around. I was now number one in line for takeoff. Let me make that very clear. The angled flight deck was probably about 600 feet long (give or take), and there were two aircraft behind me. So, maybe I had 400 feet of flight deck ahead of me.

When you do a deck run, there are only a few factors to be considered. The primary factor is the amount of wind over the deck. An anemometer measures the wind. The ship calculates the takeoff weight of the aircraft against the wind over the deck with a resulting number of feet needed to get airborne successfully. If the aircraft has the necessary amount of flight deck in front of them, then you are given the launch signal, add full power to the engines, release the brakes, and roll forward and get airborne. At least that's the way it's supposed to work.

On the 4th of February 1977, I released the brakes and rolled forward. As I went over the forward edge of the flight deck, the aircraft settled. It did not fly upwards. It settled. We flew with our overhead hatches open for all takeoffs and landing. I heard the ship's crash alarm. I looked to my right and saw the sponson above me.

Somewhere back in flight training, they taught us about the ground effect. When an aircraft is very close to the ground, the runway, or in my case the water, you get a bonus of lift, which allows you to keep in the air at airspeeds below stall speed. I knew that what I needed to do was to maintain the configuration of the aircraft with flaps set for takeoff, gear down, and hold the same attitude I was in. Don't push the nose over since I was too close to the water. Don't raise the nose because we would stall and crash. Just hold what you got and let the aircraft gain airspeed and fly itself out into safety. I did, and we made it safely ashore. Somewhere back in flight training, they taught us about the ground effect. When an aircraft is very close to the ground, the runway, or in my case the water, you get a bonus of lift, which allows you to keep in the air at airspeeds below stall speed. I knew that what I needed to do was to maintain the configuration of the aircraft with flaps set for takeoff, gear down, and hold the same attitude I was in. Don't push the nose over since I was too close to the water. Don't raise the nose because we would stall and crash. Just hold what you got and let the aircraft gain airspeed and fly itself out into safety. I did, and we made it safely ashore.

So I loaded up the passengers and came back to the ship where I made an arrested landing. I went up to the dirty shirt wardroom to grab some chow. On the line was the mini-boss. The man who had approved my clearance to takeoff some hours earlier. The man who had my life in his hands when he said we could go. He looked at me before I could even say a word.

"Anemometer was broken."

|

| |

|

What profession did you follow after your military service and what are you doing now?

|

| |

|

| Jim Tritten as Associate Professor at the Naval Postgraduate School |

I retired at the Naval Postgraduate School in 1989, where I served as a military Associate Professor and the Chairman of the Department of National Security Affairs. The next workday, I became a Department of the Navy Civilian and Associate Professor. I taught for four years and traveled around the world and wrote academic books and articles.

In 1993, I was contacted by a new organization, Naval Doctrine Command (NDC), at the Norfolk Naval Station and asked to apply for a job with them. I did, and they hired me. I did research, writing, and traveled extensively. I stayed with NDC until 1996 and awarded the Navy Superior Civilian Service Award. The first commander of NDC was Rear Admiral “Bad Fred” Lewis. A great officer and leader. He assigned me to write a study about Navy combat leadership during long periods of peace. Retired Admiral Elmo Zumwalt read the report, summoned me to his office in Northern Virginia, where he told me it was the finest piece of work to see come out of the Navy in a decade.

I was asked to apply for a new job at the U.S. Atlantic Command and was hired in 1996. I served there in their Joint Training Directorate (J7) at the Joint Training and Analysis Center (JTASC) in Suffolk, Virginia. I was awarded the Joint Chiefs of Staff Joint Meritorious Civilian Service Award for my duties as a joint training manager.

In 2002, I applied for a new position as the Department of Defense Civilian at the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) at Kirtland Air Force Base, Albuquerque, New Mexico. I was the senior person for the Agency in New Mexico and Chief of the Defense Threat Reduction University. I retired from DTRA and the civil service in 2009.

Since finishing up a 44-year career working for the Department of Defense, I re-invented myself. I switched my writing from academic and military to fiction and non-fiction, totally unrelated to anything I had ever done while I worked for the feds. I have been successful in my experiment and am currently working on a trilogy of mysteries set in New Mexico. I have won numerous writing awards for my efforts so far. Check out my author page on Amazon.com.

|

| |

|

What military associations are you a member of, if any? What specific benefits do you derive from your memberships?

|

| |

|

| Alfred Thayer Mahan Award Citation |

Air Force Association, Life Member since 1981

Association of Naval Aviation, Life Member since 1981; Board of Directors for Monterey Squadron 1986-1988

Australian Naval Institute, Associate Member 1983 1993

Disabled American Veterans, Life Member since 1991

Fleet Reserve Association, Member 1972 1975, and 1996

Marine Corps Association, Member 1995-1998

Military Officers Association of America, Life Member since 1983

Military Operations Research Society, Board of Directors, 1986-1991; Vice President (Meeting Operations), 1990-1991; Advisory Director, 1992; Member of Society 1986-1996

National Defense Industrial Association, Member since 1981

Naval Order of the United States, Life Member since 1994

Naval Intelligence Professionals, Member 1992 1994

Naval Reserve Association, Member 1970 1971

Naval Submarine League, Life Member since 1983

Navy League of the United States, Life Member since 1989

Order of Daedalians, Named Member, 1993 1994

Royal Naval Association, Associate Member 1984

Royal United Services Institute for Defence Studies, Member 1981-1995

Tailhook Association, Member 1973 75, and Life Member since 1983

The Military Conflict Institute, Member 1993-1995, and since 2002

The Naval Review, Member 1994-2002

United States Naval Institute, Life Member since 1968

I have benefited from networking opportunities and participated in publishing articles and writing contests sponsored by many of these organizations. This includes the Navy League of the United States: Alfred Thayer Mahan Award for Literary Achievement: 1986; U.S. Naval Institute the Arleigh Burke Essay Contest: Silver Medal First Honorable Mention-1986; Bronze Medal Second Honorable Mention-1991; Naval Submarine League: First Place Literary Honorarium-1989; Naval Submarine League and Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory: Plaque in recognition of contributions at Submarine Technology Symposium 1992; Military Operations Research Society: Recognition Award-1990; and Certificate of Appreciation-1991, Recognition Award-1992.

|

| |

|

In what ways has serving in the military influenced the way you have approached your life and your career? What do you miss most about your time in the service?

|

| |

|

Like any career, the Navy had its ups and downs. Hopefully, the ups compensated for the downs for most of us. My life has been shaped by where and when I was born, my early education, exposure to religion, early participation in the Boy Scouts (I am an Eagle Scout), and of course, the Navy. Early in my fleet assignments, it was the 1st Class Petty Officers and Chiefs who showed me the ropes and set me on the right path for being effective, and being a part of the team and striving for success. Like any career, the Navy had its ups and downs. Hopefully, the ups compensated for the downs for most of us. My life has been shaped by where and when I was born, my early education, exposure to religion, early participation in the Boy Scouts (I am an Eagle Scout), and of course, the Navy. Early in my fleet assignments, it was the 1st Class Petty Officers and Chiefs who showed me the ropes and set me on the right path for being effective, and being a part of the team and striving for success.

As my career continued, I had several excellent mentors and superb senior officers. While in the Navy, I finished my undergraduate education and later went on shore duty, where I earned two Master’s degrees and a Ph.D. I traded payback time for time at civilian schools undergoing higher education. The Navy was very good to me, and I would not trade my time in uniform for anything.

|

| |

|

Based on your own experiences, what advice would you give to those who have recently joined the Navy?

|

| |

|

| Retirement Ceremony at the Naval Postgraduate School 1989 |

Take a chance. Have fun. Do your job well. If you’re lucky, you will have an exciting career as I did and end up with the Danish blonde at the end.

|

| |

|

In what ways has TogetherWeServed.com helped you remember your military service and the friends you served with.

|

| |

|

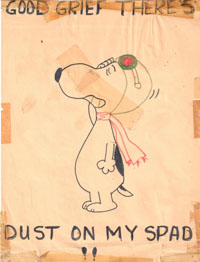

I was nominated to join TWS by a shipmate that worked for me while I was a flight instructor in VT-31. She was somewhat surprised when I sent her this photo of a drawing she had made at the time. I would have never been able to share with her that I kept it all these many years if it had not been for TWS. I was nominated to join TWS by a shipmate that worked for me while I was a flight instructor in VT-31. She was somewhat surprised when I sent her this photo of a drawing she had made at the time. I would have never been able to share with her that I kept it all these many years if it had not been for TWS.

The Spad, of course, refers to the name we used to refer to the A-1 which I flew and never cease to tell people was the best aircraft ever.

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Get Started On Together We Served

Watch our video and see what TWS is all about

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|