It didn't take long for East and West to clash after World War II. One of the first major crises of the new Cold War came in 1948 when the Soviet Union tried to cut Western-controlled West Berlin off from the rest of the world, starving its population and imposing its will on the only free city behind the Iron Curtain.

The crisis might have escalated into a full-scale war had it not been for the determination to show the international community how the Free World handles business. The Allies decided to resupply West Berlin by air, leading to a 14-month airlift sending a plane to Berlin every 30 seconds.

The crisis might have escalated into a full-scale war had it not been for the determination to show the international community how the Free World handles business. The Allies decided to resupply West Berlin by air, leading to a 14-month airlift sending a plane to Berlin every 30 seconds.

The pilots of those planes carried fuel, food, and other necessary supplies for the city, some 3,475 tons every day. One of those pilots, Gail Halvorson, dropped gifts of his own: candies for the children of Berlin. Once the news got out that an American pilot was airdropping candy over Germany, other pilots joined in, the news spread worldwide, and Halvorson became known as "The Candy Bomber."

At the time, Berlin was very deep inside Soviet-occupied Germany. The Western allies had divided the country into zones of occupation, and the Red Army controlled a large chunk of the eastern side, including the capital. Berlin itself was also cut into four zones of control, putting American, French, and British zones in the same deep hole.

As the former World War II allies rebuilt Germany, they opted to do it in a way that mirrored their own countries, with the West becoming a capitalist state and the Soviet-dominated East falling to communism. When the West introduced a new currency, the Deutsche Mark, the USSR cut off railway, road, and canal access to Berlin in an effort to force the Allies to withdraw it. The Soviets believed resupply by a narrow air bridge was unfeasible.

They were wrong, and the first battle of the new Cold War was a test of willpower. "Operation Vittles," as the Berlin Airlift was officially called, began on June 26, 1948. Pilots from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the U.S., Britain, and New Zealand took off from three airports in West Germany to deliver 2.34 million tons of vital supplies to the people of West Berlin, all day and every day for more than a year.

They were wrong, and the first battle of the new Cold War was a test of willpower. "Operation Vittles," as the Berlin Airlift was officially called, began on June 26, 1948. Pilots from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the U.S., Britain, and New Zealand took off from three airports in West Germany to deliver 2.34 million tons of vital supplies to the people of West Berlin, all day and every day for more than a year.

Halvorson was one of the regular pilots, and, despite the fame and love that his coming effort would create for him, he was originally against the whole idea. He later said he had "mixed feelings" about aiding their former enemy. Halvorson joined the Army Air Forces after the attack on Pearl Harbor, trained as a fighter pilot, and flew transport planes. During the war, he'd lost many friends to the Germans.

One day, he encountered a group of German children across the fences at the American airfield at Berlin's Tempelhof. He had two pieces of gum, which he split in half and handed to them. As he watched the children share the precious commodity, he promised to drop more the next day. As he did, he wiggled his wings.

Eventually, he started dropping candy, acquired through his own candy ration, on the city, using handkerchiefs as parachutes. When other Allied pilots and aircrews joined in, the Associated Press wrote a story about it, which led to an influx of candy and handkerchief donations from all over the Free World. They called their unofficial airdrops "Operation Little Vittles."

It wasn't until May 12, 1949, that the Soviets realized their strangulation plan wasn't going to make the Allies back down, and they lifted the blockade. Operation Little Vittles was as memorable to the people of Berlin as the airlift operation itself. Dubbed "The Candy Bomber" for the rest of his life, Halvorson was personally beloved in the German capital until he died in 2022 at age 101.

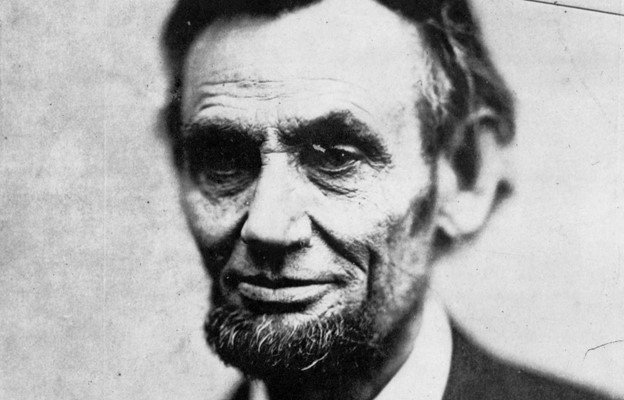

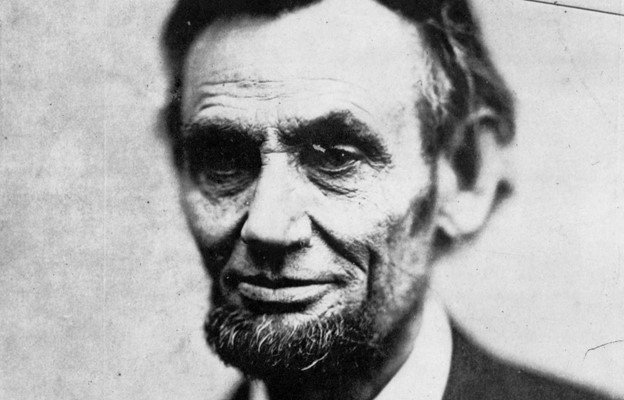

The first few years of the Civil War did not go well for the Union. At best, the war until 1863 performance could be considered a stalemate. At worst, the Confederates were establishing themselves as a force to be reckoned with. President Abraham Lincoln was looking down the barrel at a re-election campaign he never thought he would win and a country that might permanently be split in two.

Lincoln had chosen a number of generals to command the Union Army, but none of them could make any headway against the rebellion. Gen. George McClellan was an organized leader but overly cautious and allowed the Confederates to escape destruction on a few occasions. He was replaced by Gen. Henry Halleck, who was even more ineffective.

Lincoln had chosen a number of generals to command the Union Army, but none of them could make any headway against the rebellion. Gen. George McClellan was an organized leader but overly cautious and allowed the Confederates to escape destruction on a few occasions. He was replaced by Gen. Henry Halleck, who was even more ineffective.

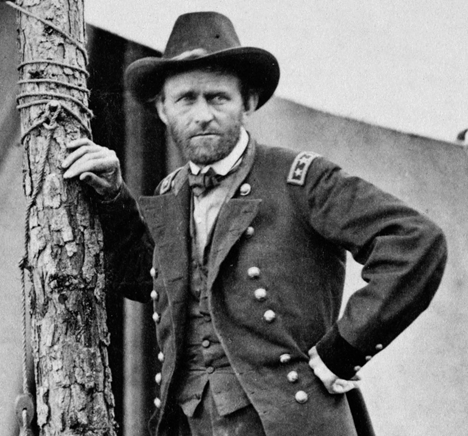

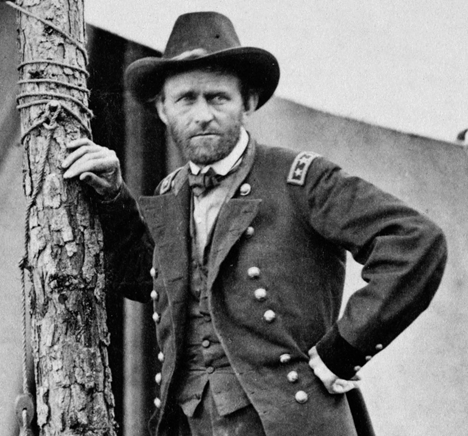

One of the few bright spots was a commander in the West, a general who had defeated the Confederates at Shiloh, Chattanooga, and gave the Union control of the Mississippi River when he captured Vicksburg, Mississippi. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was the aggressive, victorious general Lincoln needed, so the president promoted Grant to Lieutenant General, previously held only by George Washington, and put him in command of all Union forces.

Arriving in Washington in 1864, Grant's new strategy was one that would hit the Confederates on five coordinated fronts, preventing the rebels from moving men and materiel to support any single Union offensive.

Gen. William T. Sherman would destroy the rebel Army of Tennessee in the West and capture Atlanta's industrial and transportation center. Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks would attack Mobile Bay in the Gulf of Mexico while Union forces under Maj. Gen. Franz Siegel captured food supplies and transportation hubs in the Shenandoah Valley.

Grant and Gen. George G. Meade would attack the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with more than 100,000 Union troops. What would come to be known as The Overland Campaign was the beginning of the end of Lee's army and the Confederate States of America along with it.

Grant and Gen. George G. Meade would attack the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with more than 100,000 Union troops. What would come to be known as The Overland Campaign was the beginning of the end of Lee's army and the Confederate States of America along with it.

Despite how the campaign ended, it didn't start off well for the Union advance. In the first battle, a three-day fight called the Battle of the Wilderness, the rebels inflicted heavy casualties on the Union forces. Grant was forced to disengage, but a retreat was out of the question. He moved his army between Lee's and the Confederate capital of Richmond.

The move forced Lee to race to Spotsylvania Court House to prevent his army from being flanked. Another inconclusive battle raged there for nearly 12 days, but this time it was the Union who inflicted heavy casualties, losses the rebels could not replace. After Spotsylvania, Grant attempted to outflank Lee again at North Anna and then again at Cold Harbor.

Fighting at Cold Harbor raged just 10 miles from the Confederate capital. Both sides were reinforced there after suffering massive casualties until this point. Although it started off well enough for the Union, the entrenched positions built over the next 13 days meant little would be gained for either side, but the Union made repeated frontal assaults against the enemy, making Cold Harbor one of the bloodiest battles of the war, and of American military history.

Grant then laid siege to Petersburg, a critical supply line for Lee's army and for Richmond, so the rebels defended it vigorously, resulting in a nine-month siege of trench warfare. This forced Lee to extend his army to defend Petersburg while the rest of the five-point plan came to fruition.

Gen. Philip Sheridan began seizing the Shenandoah Valley in May 1864. Sherman began pushing the rebels out of Tennessee, and by the end of August, both Atlanta and Mobile Bay were under Union control. As 1864 turned to 1865, Sherman was burning the South on his March to the Sea, the Confederate Army of Tennessee was destroyed at Nashville by the undefeated Union Gen. George Henry Thomas, and President Lincoln was re-elected.

Gen. Philip Sheridan began seizing the Shenandoah Valley in May 1864. Sherman began pushing the rebels out of Tennessee, and by the end of August, both Atlanta and Mobile Bay were under Union control. As 1864 turned to 1865, Sherman was burning the South on his March to the Sea, the Confederate Army of Tennessee was destroyed at Nashville by the undefeated Union Gen. George Henry Thomas, and President Lincoln was re-elected.

The ongoing Siege of Petersburg had forced Lee's army to extend its lines by 35 miles. Lee was trapped, losing troops to desertion and starvation. On April 1, 1865, Grant began attacking the Petersburg lines, which collapsed against the offensive. Two days later, Union troops entered Richmond.

In a last-ditch effort to save his army, Lee tried to link up with Gen. Joseph E. Johnston, but Sheridan cut them off and captured their supplies. With no hope of reinforcements and his men starving, Lee sent Grant a letter to discuss the terms of his surrender, effectively ending the Civil War.

I have been able to touch base with some of my shipmates whom I have not communicated with in years. This is a great website that is secure so that I can place items, photos, and remembrances of my military career. More importantly, it is fun and also humbling to see what others have done in the service of their country. Thanks to all who have served and continue to serve.

Capt James Garrett US Navy (Ret)

Served 1966-2008

Even though movies and television are supposed to be an escape from reality for a little while, veterans watching military movies will often have a hard time looking away from the train wrecks of military uniforms in those shows.

The offenses can be small, such as uniforms wearing the wrong service's ribbons and medals, to the egregious, like wearing uniform items that don't even exist. Some movies even feature characters wearing the camouflage of a different country.

The offenses can be small, such as uniforms wearing the wrong service's ribbons and medals, to the egregious, like wearing uniform items that don't even exist. Some movies even feature characters wearing the camouflage of a different country.

One rumor that has persisted for decades is that Hollywood actually has to get military uniforms wrong in some ways, lest they be on the wrong side of some stolen valor charge. The rumor says that there is a federal statute of Department of Defense litigation that prevents studios from using proper uniforms.

With some of the terrible uniforms depicted in some movies and shows, who could blame anyone for seeing the logic in that? The truth is that there is no such law or regulation; Hollywood is just really bad at military uniforms. Sometimes, they would rather their character look cooler with his OCPs hanging open than looking like a real troop.

This belief isn't entirely false, however. 10 U.S. Code § 772, the law that dictates when military uniforms are authorized to wear, used to have a section that restricted when actors could wear them onscreen. They were allowed only "if the portrayal does not tend to discredit that armed force."

This belief isn't entirely false, however. 10 U.S. Code § 772, the law that dictates when military uniforms are authorized to wear, used to have a section that restricted when actors could wear them onscreen. They were allowed only "if the portrayal does not tend to discredit that armed force."

Well, it wasn't long before someone challenged that portion of the law. In 1970, a man named Schacht was convicted of breaking that law in a skit that was demonstrating against the war in Vietnam. He was sentenced to pay a fine of $250 and to serve a six-month prison term.

Schacht took his case to the Supreme Court, which overturned the conviction and ruled that part of the law unconstitutional on First Amendment grounds. Specifically, it was based on his First Amendment rights to criticize the government.

With that law out of the way, Hollywood (and pretty much everyone else) were free to wear uniforms however they wanted. As we all know, they sometimes get them terribly, terribly wrong. Other times, the shows are being made by people who want as much truth and accuracy as possible.

These productions enlist the help of the armed forces or hire a military advisor to do that kind of work for them, making it much, much easier on the eyes and souls of the veterans who watch them.

By: A3C Michael S. Bell

The 442nd Infantry Regiment was constituted on June 4, 1942, as the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate). It was activated on June 12, 1942, at Oakland, California, with personnel from the Hawaiian Provisional Infantry Battalion. "The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was organized on March 23, 1943. Within a month, 2,686 volunteers from Hawai'i and 1,500 from the U.S. mainland were in Camp Shelby,  Mississippi, for basic training. The 442nd included three infantry battalions, the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 232nd Combat Engineers Company, an Anti Tank Company, a Cannon Company, Medical Detachment, and the 206th Army Ground Forces Band. On May 1, 1944, the RCT, minus the 1st Battalion, left for Italy, where it joined the 100th Infantry Battalion just north of Rome. The 1st Battalion had been sending troops to replace the killed and wounded in the 100th, and its ranks were substantially depleted; the men still in the Battalion were reserved in place as training officers for the next group of volunteers at Shelby. The 442nd entered combat north of Rome in June 1944 when it incorporated the 100th Battalion, which, because of its outstanding combat record, was allowed to keep its designation. Thus, the infantry units in the RCT were the 100th, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions. The 442nd was attached to the 5th Army."

Mississippi, for basic training. The 442nd included three infantry battalions, the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 232nd Combat Engineers Company, an Anti Tank Company, a Cannon Company, Medical Detachment, and the 206th Army Ground Forces Band. On May 1, 1944, the RCT, minus the 1st Battalion, left for Italy, where it joined the 100th Infantry Battalion just north of Rome. The 1st Battalion had been sending troops to replace the killed and wounded in the 100th, and its ranks were substantially depleted; the men still in the Battalion were reserved in place as training officers for the next group of volunteers at Shelby. The 442nd entered combat north of Rome in June 1944 when it incorporated the 100th Battalion, which, because of its outstanding combat record, was allowed to keep its designation. Thus, the infantry units in the RCT were the 100th, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions. The 442nd was attached to the 5th Army."

The regimental motto most often associated with the 442nd IR, "Go for Broke," as presented on the unit’s DUI, originated in slang used during gambling, perhaps especially in Craps, to denote going all in, "shooting the works," risking everything on one roll of dice in betting. It is not readily known who started the tradition in the regiment or if it was simply spontaneous. The phrase became something of a rallying cry amongst stateside Japanese in America as well during WWII, cheering on their team in battle despite government-imposed extreme deprivations being endured here at home. On February 19, 1942, FDR issued Executive Order 9066, which led to the forced relocation of approximately 120,000 Japanese living on the West Coast. More than two-thirds of these people were native-born citizens. Japanese had been coming to North America since the late 1500s, and the first to reach present-day California arrived in 1815. The nickname sometimes attributed to this unit, "Purple Heart Battalion," belongs to the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), which was a component of the 442nd IR. Poignantly, their Regimental Combat Team’s SSI depicts Lady Liberty’s upraised hand and torch, offering a beacon for all who seek freedom.

442nd RCT fight song excerpt, the version provided by 442nd Veterans Club, sung to the tune of the US Coast Guard anthem, lyrics by: Martin Kida, KIA

442nd RCT fight song excerpt, the version provided by 442nd Veterans Club, sung to the tune of the US Coast Guard anthem, lyrics by: Martin Kida, KIA

"All hail, all hail our combat team: the finest in the land.

Thru storm or rain, in peace or war for freedom, we shall stand.

We come from far-off Aloha Land: The Land of Paradise.

Hawai'i, Hawai'i: Pacific paradise.

Hawai'i, Hawai'i: Pacific paradise.

Four Forty-Second Infantry: We're the boys from Hawai'i nei.

We're fighting for you and the red, white, and blue.

We're going to the front and back to Honolulu-lulu.

Fight for dear ol' Uncle Sam.

Go For Broke, we don't give a damn.

Let them come and run at the point of our gun:

For freedom must be won.

I lai-lai (I lai-ai lai)

I lai-lai (I lai-ai lai)

I lai-lai lai-ai, lai la-lai-lai lai)

I lai-lai (I lai-ai lai)

I lai-lai (I lai-ai lai)…"

Training at Camp Shelby that began in 1943 ended in April 1944, and by June, they were in Italy against German positions in Tuscany. In September of that year, the 442nd participated in liberating southern France, having fought alongside the African American 92nd Infantry Division, driving Germans out of northern Italy, toward the Arno River, in the areas of Belvedere, Sassetta, Cecina, and Castellina Marittima (Hill 140 "Little Cassino") advancing a distance of only 40 costly miles. By the time they crossed the Arno, they’d suffered 17 missing, 44 non-combat injuries, 972 WIA, and 239 KIA. In late October, their anti-tank detachment rejoined the unit during a battle to find  and liberate the "Lost Battalion." After leaving Naples, the 442nd landed at Marseille, having moved 500 miles on foot and by train through the Rhone Valley into position for the assault on Bruyeres and the Vosges Mountain range, with battle results going back and forth between opposing forces, taking and retaking of objectives, being called into action at Biffontaine, engaging in house-to-house warfare and tactics for nine days before they came to attempt the rescue of the "lost" 141st Alamo Regiment which had been cut off behind enemy lines, in the heaviest fighting the 442nd had seen. The valor of Nisei charging German emplacements beyond the breaking of enemy defenses, all the way to Saint-Die, undergoing tremendous losses on both sides, remains among the most memorable combined land forces assaults in US Army history. The regiment then headed to the Maritime Alps of the Riviera, patrolling a 14-mile segment of the French-Italian border with comparatively incidental casualties.

and liberate the "Lost Battalion." After leaving Naples, the 442nd landed at Marseille, having moved 500 miles on foot and by train through the Rhone Valley into position for the assault on Bruyeres and the Vosges Mountain range, with battle results going back and forth between opposing forces, taking and retaking of objectives, being called into action at Biffontaine, engaging in house-to-house warfare and tactics for nine days before they came to attempt the rescue of the "lost" 141st Alamo Regiment which had been cut off behind enemy lines, in the heaviest fighting the 442nd had seen. The valor of Nisei charging German emplacements beyond the breaking of enemy defenses, all the way to Saint-Die, undergoing tremendous losses on both sides, remains among the most memorable combined land forces assaults in US Army history. The regiment then headed to the Maritime Alps of the Riviera, patrolling a 14-mile segment of the French-Italian border with comparatively incidental casualties.

The last German defense in Italy against the hard-driving Nisei was Monte Nebbione, south of Aulia. The unit’s final push in April finally took that objective and Mount Carbolo. Following the fall of San Terenzo, the 2nd Battalion and Task Force Fukuda pincered to cut off a German retreat there, resulting in enemy surrender by the hundreds and thousands to our Fifth and Eighth Armies. This was the final action of the 442nd in the ETO of World War II, which ended on May 2.

Over 33,000 Japanese-Americans served in the U.S. Military during WWII, with more than 800 giving their lives for their country; ultimately, about 18,000 served with the 442nd IR/RCT over the full course of its formation. In less than two years of battle, members of the unit received 4,000 purple hearts, 560 Silver Stars, 52 DSCs, a DSM, 15 Soldier’s Medals, 4,000 Bronze Stars, and 21 MOHs. The unit itself was awarded seven, five in one month, PUCs and the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010 to the RCT. In 2012 all surviving members were made chevaliers of the French Legion d’Honneur. In total, members of the 442nd received 18,143 awards during their relatively brief time. April 5 is celebrated as National "Go For Broke Day." The venerable Representative and Senator Daniel Inouye of Hawaii is counted among its outstanding alumni. It has been stated that the 100th/442nd RCT is the most decorated unit for its size and duration of service in our history.

Despite their heroism and sacrifice, these soldiers, and by inference, their ancestors, experienced humiliations that were in no way deserved. Two incidents must be reported if only to demonstrate how far beyond those dark times America has evolved in the 80 years since then:

Despite their heroism and sacrifice, these soldiers, and by inference, their ancestors, experienced humiliations that were in no way deserved. Two incidents must be reported if only to demonstrate how far beyond those dark times America has evolved in the 80 years since then:

- In 1946, the American Legion refused to allow Nisei veterans into their ranks and removed them from the Honor Rolls. White officers of the 100th/442nd intervened, and gradually those names were restored.

- The General Dahlquist episode late in the war is remembered. In mid-November, as Division Commander, he ordered the 442nd to stand in formation for recognition and awards. Of the four hundred troops originally assigned, only eighteen survivors of K Co. and eight of I Co. turned out. The General lost his composure and demanded of Col. Virgil Miller, "I want all your men to stand for this formation." To which the Colonel replied, "That’s all of K company left, sir." The Commander had been regarded as one who treated these soldiers as cannon fodder. "Sometime later, while the former Commander of the 1st Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Gordon Singles, was filling the role of Brigadier General at Fort Bragg (North Carolina), General Dahlquist arrived as part of a review. When he recognized Colonel Singles, he approached him and offered the Colonel his hand, saying, ‘Let bygones be bygones. It's all water under the bridge, isn't it?’ In the presence of the entire III Corps, Colonel Singles continued to salute General Dahlquist but refused to take Dahlquist's hand."

The 442nd was inactivated in 1946, reactivated in 1947 to the Reserves, and mobilized again in 1968 during the Vietnam War, carrying on the unit’s traditions and honors as the only ground combat unit of the U.S. Army Reserve and headquartered at Fort Shafter, Hawaii with two companies detached in American Samoa. Part of the unit was mobilized for duty during OIF at Balad, Iraq, between 2004-08, receiving the MUC for their actions and losing five more KIA in the ranks. In 2009 it was deployed once more as an element of the 29th Inf Brigade Combat Team to Kuwait, suffering two more losses. During this assignment, several dozen of the unit’s Samoan troops became naturalized U.S. Citizens.

The 442nd was inactivated in 1946, reactivated in 1947 to the Reserves, and mobilized again in 1968 during the Vietnam War, carrying on the unit’s traditions and honors as the only ground combat unit of the U.S. Army Reserve and headquartered at Fort Shafter, Hawaii with two companies detached in American Samoa. Part of the unit was mobilized for duty during OIF at Balad, Iraq, between 2004-08, receiving the MUC for their actions and losing five more KIA in the ranks. In 2009 it was deployed once more as an element of the 29th Inf Brigade Combat Team to Kuwait, suffering two more losses. During this assignment, several dozen of the unit’s Samoan troops became naturalized U.S. Citizens.

Between 1951 and 2018, six films were produced using "Go For Broke" in their titles, while fictional and documentary television series have featured its members. Among several books that have included extensive passages about the 442nd, James Michener’s "Hawaii" devotes a full chapter, not to mention the biographical and historical publications written and to be written. Commemorative monuments, such as the one in Los Angeles illustrated above, are dedicated to the 442nd here and abroad, as are specific highways in America and Europe. Asian Americans fought for both sides during our Civil War and every other war since that period. In 2023, the estimated number of living WWII 442nd veterans stands at about four hundred, most of whom live in Hawaii. These soldiers long ago earned their rightful place among the highest echelons of devotion and bravery known to the United States Army.

Talking to the other Vets has reminded me of my bond with those I served with. TWS is a great place to meet people like yourself!

Sgt Robert Center US Air Force Veteran

Served 1965-1969

The website aims to transform the customer experience for those seeking to sell to or innovate with VA.

The website aims to transform the customer experience for those seeking to sell to or innovate with VA.

WASHINGTON - The Department of Veterans Affairs launched Pathfinder.va.gov in early June, serving as the "front door" for vendors and innovators to engage with VA while providing useful resources.

Via the Pathfinder website, users can submit their innovative ideas, solutions, products, or services - and provide information about themselves, their company, or their organization.

"This is a focused point of entry to selling and innovating with VA for our industry partners," said VA Chief Acquisition Officer Michael Parrish. "It fills a gap we've found in the acquisition lifecycle by creating the fusion of acquisition and innovation with this intelligent system."

Pathfinder allows an opportunity for VA to move forward in vendor engagements in a way that is unprecedented. It supports a backend system that ensures vendors have transparency, equity, and support throughout the entire process in a timely and visible manner. This also improves VA's response time to companies or individuals looking for the status of their submission.

"In order for VA to provide the highest quality care to Veterans, we must offer a more customer-focused pathway to engage industry, academia, and Veteran advocates who are actively working to solve Veteran and health care challenges," said VA's Office of Healthcare Innovation and Learning Community Engagement Director Suzanne Shirley. "Our goal is to remove barriers and assist vendors and innovators in navigating the organization while collaboratively improving care and services for Veterans and their caregivers."

"Pathfinder provides the road map to allow interested businesses of all sizes to understand the landscape and processes of identifying opportunities, and it walks them through the process with a real interaction," said VA's Director of Category Management Support Office Ernest Reed, Ph.D. "This allows VA to move forward in vendor engagements in a way that is unprecedented. Many vendors have never experienced the process of doing business with VA or the federal government."

VA's Offices of Acquisition, Logistics and Construction, Healthcare Innovation and Learning, and Information and Technology are leading this initiative to transform the user experience. VA will use submissions to conduct market research, build an innovation solution repository for continuous sourcing and match the innovative solutions from the repository with VA problem spaces. Get information for Pathfinder.va.gov.

By Logan Nye

We Are The Mighty

If you were to fall asleep near the ITER Tokamak, get bombarded by exotic nuclear particles, and be transported back in time to 1942, what job would you choose? Would you take part in World War II? Would you work in a factory? Join the U.S. Merchant Marine? Enlist in His Majesty’s Armed Forces?

Statistically, according to a Great Courses lecture series by the University of Pennsylvania Professor Thomas Childers, three jobs were more dangerous than any others. Pick one of these three, and it would be nearly certain that you wouldn’t make it back to your time portal alive.

If you choose either of the first two after reading this article, I applaud your theoretical courage. But if you chose the third, I’m closing the time portal. You made your bed. You can lie in it. I’ll peek in to check on you roundabouts at the time of the Nuremberg Trials.

U.S. Army Air Corps Bomber Crew

U.S. Army Air Corps Bomber Crew

A tour of duty for U.S. bomber airmen in World War II was 25 bombing missions. But the life expectancy of an 8th Air Force crew member in 1944 was just 15 missions. And that was an improvement. In its first year of combat, the 8th Air Force only saw 30% of its crew members finish their quota alive.

It’s easy to understand the risks they faced. Strategic bombers initially lacked fighter support on many missions. They flew in large, defensive boxes that were easy to spot from the ground and fire at with flak. German fighters could race up to the clouds to attack them. If they could get the formation to break, the defensive box would fail, and the fighters could down them relatively safely.

Meanwhile, the environment was so hostile that a crew member could die of oxygen deprivation if they took off their mask and it failed. Or they risked instant frostbite if they lost a glove.

RAF Bomber Crew

We don’t need to go too deep into this, right? Royal Air Force crew members faced very similar trials to their Yank counterparts. German fighters, flak emplacements, and a hostile environment.

Crucially, they did fight alone for a few years, though, from the fall of France in 1939 to the German invasion of the USSR and the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor in 1941. And Royal Air Force crews were obligated for 30 missions, not 25.

All-in-all, the Imperial War Museum says that 51% died in combat, 12% were killed or wounded outside of combat, and only 24 percent survived.

German U-Boat Crew

German U-Boat Crew

Now do you see why I said that I only had respect for folks who picked jobs one or two? German U-boat crews could arguably have done the whole world a favor by deserting with their boats. But those who did stand firm faced an amazingly dangerous role.

The wolfpack crews had a huge impact early in the war. But U-boats were mechanically fraught, with at least one sinking because a commander tried to flush his own toilet. British innovations in surface radar and sonar soon made the hunters the hunted. When they came under attack, crews knew that any serious damage to the boat would force them to the surface or the seafloor.

The men who served in any of these three roles displayed amazing bravery.

Read the original story on We Are The Mighty.

By We Are The Mighty

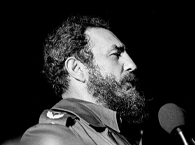

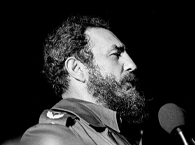

In April 1961, 1,500 Cuban exiles landed on the southwestern coast of Cuba. Just two years prior, rebel leader Fidel Castro took power in Havana after years of revolutionary combat. Unlike revolutions on the island in the past, Castro was a communist, and his revolution nationalized American businesses, which included industries like oil, sugar, and coffee. The U.S. government was not pleased.

President Eisenhower enacted an embargo on Cuba while the CIA began funding Brigade 2506, an armed insurgency group dedicated to overthrowing Castro and reinstating democratic rule in Cuba. By the time the invasion was ready, it consisted of 1,500 exiles. CIA B-26 bombers hit Cuban airfields two days before the invasion. It did not go well for the exiles.

President Eisenhower enacted an embargo on Cuba while the CIA began funding Brigade 2506, an armed insurgency group dedicated to overthrowing Castro and reinstating democratic rule in Cuba. By the time the invasion was ready, it consisted of 1,500 exiles. CIA B-26 bombers hit Cuban airfields two days before the invasion. It did not go well for the exiles.

On April 17, 1961, five battalions of troops landed at the Bay of Pigs, backed by Cuban pilots. It overwhelmed the local militia, but Fidel Castro took personal command of the counterattack. The plan required support from U.S. naval and air forces, but when the world learned what was happening, President John F. Kennedy withheld that support. All the Cuban exiles had for air cover were Cuban pilots.

On the last day of the invasion, April 20, Cuban pilots were exhausted from their efforts. With their democratic fighters dying on the ground, four pilots from the Alabama Air National Guard and four enlisted crew members volunteered to take over in four of the Cuban exiles' bomber aircraft.

The Alabama National Guard had been part of the operation for a long time before the actual Bay of Pigs invasion. The governor of Alabama had approved the use of National Guard personnel to assist the CIA in 1960. It was the Alabama ANG who trained the Cuban exiles to fly and fight in the Douglas B-26 Invader bomber. Alabama was the last state guard who was flying the B-26.

Because Kennedy had restricted the number of bomber aircraft that could attack Cuba before the invasion, only half of Castro's air force was destroyed in the initial attack. The rest of the air forces were able to destroy the fuel and supplies for the invasion that were waiting offshore aboard merchant ships after the initial bombing run.

When the Bay of Pigs inva sion came, the Cuban exiles were ambushed by Castro's air forces. They lost five of their 16 bombers on the first day. When they returned to the secret airbase in Nicaragua, Alabama guardsmen repaired, refueled, and rearmed them before they made the six-hour flight back to Cuba. With a manpower shortage in the air, Kennedy finally relented and allowed American pilots to assist.

sion came, the Cuban exiles were ambushed by Castro's air forces. They lost five of their 16 bombers on the first day. When they returned to the secret airbase in Nicaragua, Alabama guardsmen repaired, refueled, and rearmed them before they made the six-hour flight back to Cuba. With a manpower shortage in the air, Kennedy finally relented and allowed American pilots to assist.

When the CIA gave the green light to the Alabama guard, eight of them stepped forward to volunteer. Maj. Billy "Dodo" Goodwin led the group with pilots Joe Shannon, Riley Shamburger, and Thomas Willard "Pete" Ray and Alabama crewmembers Leo F. Baker, Wade Gray, Nick Sedano, and James Vaughn. When the American-run planes began their approach, they were swarmed by Castro's fighters. Riley Shamburger and his crewmember Wade Gray were shot down over water. Their bodies could not be recovered.

Ground fire from Cuban gunners brought down pilot Pete Ray and crewmember Leo F. Baker. They survived their crash landing but were killed by Castro's Cuban revolutionaries in a firefight after landing. The remaining aircraft left the area. Later that same day, the invasion ended in failure. The invaders that survived were held for ransom until 1963. Pete Ray's body was held in Cuba for another 17 years.

Read the story on We Are The Mighty.

TWS is a great vehicle for sharing your life experiences in and out of the military. It's therapeutic in many ways to relive your history through TWS.

GMC Jory Luchsinger US Coast Guard Reserves (Ret)

Served 1965-2001

Remembering is Easy, Telling the Story is Difficult

By Bob Olsen

Every year since WWII, people have watched programs depicting war stones from that period. Although some are true, the real truth is that each person who was there, who participated in this moment in history, has their own real, personal war story. It was no different with Bill Lewis. I have heard some war stories, some from him and some from TV. However, my memory was confused about which stories I had heard from Bill. So, upon returning to my hometown, I stopped by to talk once again to my childhood neighbor Bill about HIS war.

Bill: Daily, the memories flood back, often at times when they are least wanted and thus blocking out important relationships, discussions, or, at the very least, quiet times for myself. They are haunting and unwanted, yet they are deeply embedded and so very personal. Because I was there, it really was me. Oh God, what friends I lost and the things I saw and did. I have settled it within myself a thousand times, maybe more, and yet the memories continue. How is it that I was the one to return while so many of my friends did not? Am I blessed or cursed with these memories?

Bill: Daily, the memories flood back, often at times when they are least wanted and thus blocking out important relationships, discussions, or, at the very least, quiet times for myself. They are haunting and unwanted, yet they are deeply embedded and so very personal. Because I was there, it really was me. Oh God, what friends I lost and the things I saw and did. I have settled it within myself a thousand times, maybe more, and yet the memories continue. How is it that I was the one to return while so many of my friends did not? Am I blessed or cursed with these memories?

As we sat and talked, it became obvious that he had not told much of his story to anyone but instead had lived with his memories for all these years. Bill's wife. Barbara and their son, John, listened when I asked him to tell of HIS war. After some coaxing, he said he had been in the European Theater. I asked where? He said, "Omaha Beach"~[long pause] After a moment, I asked when? He said, "On D-Day," In unison. Barbara, John, and I all dropped our jaws. It was obvious the flood of memories came back, and I could see his eyes tearing up. I asked what rank he was when he went in. He said, "PFC, I was a cannon loader on a Sherman tank." I asked what rank he was as the war ended. He answered, "Staff Sergeant in charge of three tanks," Barbara said that he must have done very well to get those promotions. With tears in his eyes, Bill looked at each of us and said quietly, "A lot of guys died."

His statement was simple but profound. "A lot of guys died." Take a moment of your time and think about this statement. Those who died were husbands, fathers, sons, and daughters who all had THEIR war. Amazingly, THEIR WAR and THEIR STORY, but it was FOR ALL OF US!

Too soon, we forget the price that was paid by so many. Too soon, we forget to ask about THEIR WAR. Too late, we take the time to listen. Maybe it's time for you to ask a Veteran about THEIR WAR. Memorial Day is a time for remembering and giving thanks to our armed services: those who paid the ultimate price for our freedom.

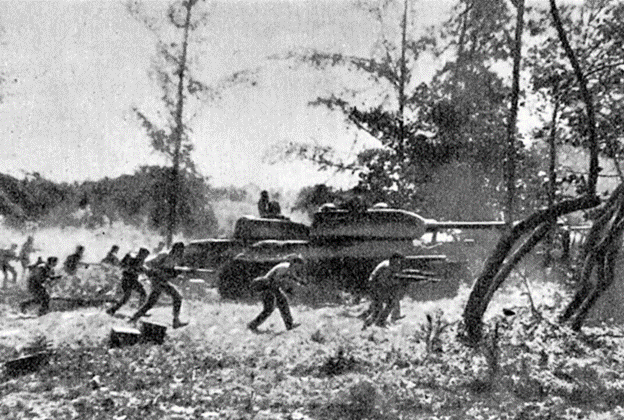

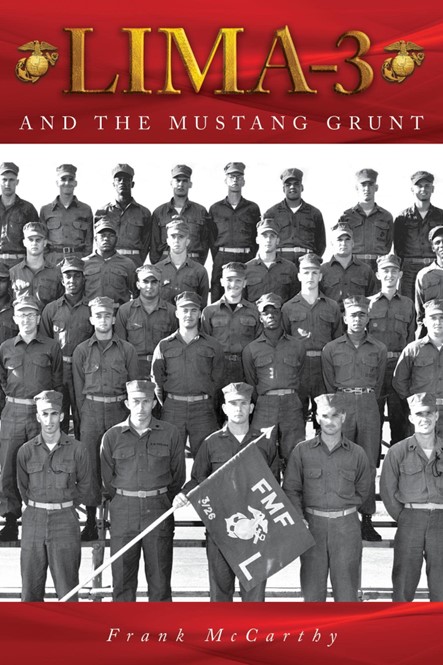

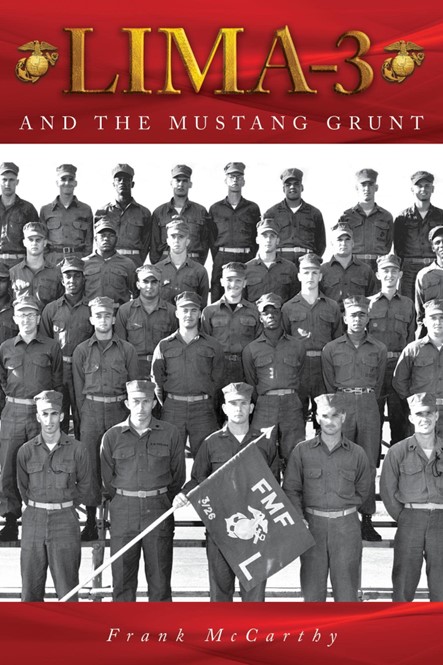

by Frank McCarthy

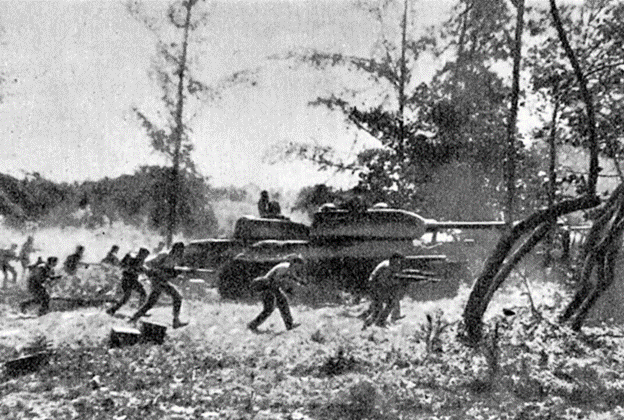

Thirteen months in Vietnam is a long time for anyone to be deployed. For the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines in 1966, it probably seemed like an eternity. Maj. (ret.) Frank McCarthy's book "Lima-3 and the Mustang Grunt" vividly describes what it was like to fight against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam.

Thirteen months in Vietnam is a long time for anyone to be deployed. For the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines in 1966, it probably seemed like an eternity. Maj. (ret.) Frank McCarthy's book "Lima-3 and the Mustang Grunt" vividly describes what it was like to fight against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam.

His book tells the story of his company, Lima Company, from the formation of the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines at Camp Pendleton all the way through their rotation home, all reflectively written from the view of then-Lt. Frank McCarthy. It even includes dozens of photographs from the unit.

Lima Company (and the rest of the Marines making the sea voyage to Vietnam) were caught up in Typhoon Ida on their journey to the war. Ida killed an estimated 275 people and sank 107 seagoing ships, but luckily not the transport carrying McCarthy's Marines. They arrived in Vietnam in December 1966 after 80 hours in a typhoon, well-trained but with zero combat experience.

That soon changed. Within days, McCarthy and his Marines were headed to the Co Bi-Thanh Tan corridor, where the Viet Cong had just struck three South Vietnamese strongpoints. With the North Vietnamese Army attempting to infiltrate the area, the 3rd Battalion was headed into action.

They didn't wait for very long before the Viet Cong struck. On Dec. 22 and 23, 1966, the 802d VC Battalion launched large attacks against the Marines. The ongoing operation was expanded into Operation Chinook, a 90-day effort to eliminate enemy forces south of the DMZ. There, Lima Company and the rest of the Marines fought against a determined enemy in monsoon weather, covered in leeches, shivering in foxholes, and avoiding mines and booby traps.

McCarthy recalls the unit's exploits through some of the most enduring names in the history of the Vietnam War, from Phu Bai, Con Tien, and then to Khe Sanh and back from both his own memory and official records. The result is a stunning firsthand view of what it was like to lead Marines in the earliest days of the Vietnam War.

"Every time something came up, they said 'send in the 26th Marines," remembered Lee Solomon, a veteran from Lima Company. "We lived in the jungle. We didn't have an area of operations. We were nomads in-country, and everywhere we went, we were in a fight. I spent 19 months in combat there, and that's all I did the whole time."

"Every time something came up, they said 'send in the 26th Marines," remembered Lee Solomon, a veteran from Lima Company. "We lived in the jungle. We didn't have an area of operations. We were nomads in-country, and everywhere we went, we were in a fight. I spent 19 months in combat there, and that's all I did the whole time."

In his book, McCarthy shares some of the harrowing war stories that can only come from someone who spent significant time in the field. McCarthy and his men, many of them just 18 years old, endured some of the hardest fighting of the war in some of the worst conditions imaginable.

A lot of books will give history buffs and Vietnam War enthusiasts a 30,000-foot view of the battles and campaigns of U.S. forces in South Vietnam. Many more will also tell stunning stories about individuals' experiences in the war.

The crisis might have escalated into a full-scale war had it not been for the determination to show the international community how the Free World handles business. The Allies decided to resupply West Berlin by air, leading to a 14-month airlift sending a plane to Berlin every 30 seconds.

The crisis might have escalated into a full-scale war had it not been for the determination to show the international community how the Free World handles business. The Allies decided to resupply West Berlin by air, leading to a 14-month airlift sending a plane to Berlin every 30 seconds. They were wrong, and the first battle of the new Cold War was a test of willpower. "Operation Vittles," as the Berlin Airlift was officially called, began on June 26, 1948. Pilots from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the U.S., Britain, and New Zealand took off from three airports in West Germany to deliver 2.34 million tons of vital supplies to the people of West Berlin, all day and every day for more than a year.

They were wrong, and the first battle of the new Cold War was a test of willpower. "Operation Vittles," as the Berlin Airlift was officially called, began on June 26, 1948. Pilots from Australia, Canada, South Africa, the U.S., Britain, and New Zealand took off from three airports in West Germany to deliver 2.34 million tons of vital supplies to the people of West Berlin, all day and every day for more than a year.

Lincoln had chosen a number of generals to command the Union Army, but none of them could make any headway against the rebellion. Gen. George McClellan was an organized leader but overly cautious and allowed the Confederates to escape destruction on a few occasions. He was replaced by Gen. Henry Halleck, who was even more ineffective.

Lincoln had chosen a number of generals to command the Union Army, but none of them could make any headway against the rebellion. Gen. George McClellan was an organized leader but overly cautious and allowed the Confederates to escape destruction on a few occasions. He was replaced by Gen. Henry Halleck, who was even more ineffective.  Grant and Gen. George G. Meade would attack the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with more than 100,000 Union troops. What would come to be known as The Overland Campaign was the beginning of the end of Lee's army and the Confederate States of America along with it.

Grant and Gen. George G. Meade would attack the Army of Northern Virginia under the command of Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee with more than 100,000 Union troops. What would come to be known as The Overland Campaign was the beginning of the end of Lee's army and the Confederate States of America along with it.  Gen. Philip Sheridan began seizing the Shenandoah Valley in May 1864. Sherman began pushing the rebels out of Tennessee, and by the end of August, both Atlanta and Mobile Bay were under Union control. As 1864 turned to 1865, Sherman was burning the South on his March to the Sea, the Confederate Army of Tennessee was destroyed at Nashville by the undefeated Union Gen. George Henry Thomas, and President Lincoln was re-elected.

Gen. Philip Sheridan began seizing the Shenandoah Valley in May 1864. Sherman began pushing the rebels out of Tennessee, and by the end of August, both Atlanta and Mobile Bay were under Union control. As 1864 turned to 1865, Sherman was burning the South on his March to the Sea, the Confederate Army of Tennessee was destroyed at Nashville by the undefeated Union Gen. George Henry Thomas, and President Lincoln was re-elected.

The offenses can be small, such as uniforms wearing the wrong service's ribbons and medals, to the egregious, like wearing uniform items that don't even exist. Some movies even feature characters wearing the camouflage of a different country.

The offenses can be small, such as uniforms wearing the wrong service's ribbons and medals, to the egregious, like wearing uniform items that don't even exist. Some movies even feature characters wearing the camouflage of a different country.  This belief isn't entirely false, however. 10 U.S. Code § 772, the law that dictates when military uniforms are authorized to wear, used to have a section that restricted when actors could wear them onscreen. They were allowed only "if the portrayal does not tend to discredit that armed force."

This belief isn't entirely false, however. 10 U.S. Code § 772, the law that dictates when military uniforms are authorized to wear, used to have a section that restricted when actors could wear them onscreen. They were allowed only "if the portrayal does not tend to discredit that armed force."

Mississippi, for basic training. The 442nd included three infantry battalions, the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 232nd Combat Engineers Company, an Anti Tank Company, a Cannon Company, Medical Detachment, and the 206th Army Ground Forces Band. On May 1, 1944, the RCT, minus the 1st Battalion, left for Italy, where it joined the 100th Infantry Battalion just north of Rome. The 1st Battalion had been sending troops to replace the killed and wounded in the 100th, and its ranks were substantially depleted; the men still in the Battalion were reserved in place as training officers for the next group of volunteers at Shelby. The 442nd entered combat north of Rome in June 1944 when it incorporated the 100th Battalion, which, because of its outstanding combat record, was allowed to keep its designation. Thus, the infantry units in the RCT were the 100th, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions. The 442nd was attached to the 5th Army."

Mississippi, for basic training. The 442nd included three infantry battalions, the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, the 232nd Combat Engineers Company, an Anti Tank Company, a Cannon Company, Medical Detachment, and the 206th Army Ground Forces Band. On May 1, 1944, the RCT, minus the 1st Battalion, left for Italy, where it joined the 100th Infantry Battalion just north of Rome. The 1st Battalion had been sending troops to replace the killed and wounded in the 100th, and its ranks were substantially depleted; the men still in the Battalion were reserved in place as training officers for the next group of volunteers at Shelby. The 442nd entered combat north of Rome in June 1944 when it incorporated the 100th Battalion, which, because of its outstanding combat record, was allowed to keep its designation. Thus, the infantry units in the RCT were the 100th, 2nd, and 3rd Battalions. The 442nd was attached to the 5th Army." 442nd RCT fight song excerpt, the version provided by 442nd Veterans Club, sung to the tune of the US Coast Guard anthem, lyrics by: Martin Kida, KIA

442nd RCT fight song excerpt, the version provided by 442nd Veterans Club, sung to the tune of the US Coast Guard anthem, lyrics by: Martin Kida, KIA and liberate the "Lost Battalion." After leaving Naples, the 442nd landed at Marseille, having moved 500 miles on foot and by train through the Rhone Valley into position for the assault on Bruyeres and the Vosges Mountain range, with battle results going back and forth between opposing forces, taking and retaking of objectives, being called into action at Biffontaine, engaging in house-to-house warfare and tactics for nine days before they came to attempt the rescue of the "lost" 141st Alamo Regiment which had been cut off behind enemy lines, in the heaviest fighting the 442nd had seen. The valor of Nisei charging German emplacements beyond the breaking of enemy defenses, all the way to Saint-Die, undergoing tremendous losses on both sides, remains among the most memorable combined land forces assaults in US Army history. The regiment then headed to the Maritime Alps of the Riviera, patrolling a 14-mile segment of the French-Italian border with comparatively incidental casualties.

and liberate the "Lost Battalion." After leaving Naples, the 442nd landed at Marseille, having moved 500 miles on foot and by train through the Rhone Valley into position for the assault on Bruyeres and the Vosges Mountain range, with battle results going back and forth between opposing forces, taking and retaking of objectives, being called into action at Biffontaine, engaging in house-to-house warfare and tactics for nine days before they came to attempt the rescue of the "lost" 141st Alamo Regiment which had been cut off behind enemy lines, in the heaviest fighting the 442nd had seen. The valor of Nisei charging German emplacements beyond the breaking of enemy defenses, all the way to Saint-Die, undergoing tremendous losses on both sides, remains among the most memorable combined land forces assaults in US Army history. The regiment then headed to the Maritime Alps of the Riviera, patrolling a 14-mile segment of the French-Italian border with comparatively incidental casualties.  Despite their heroism and sacrifice, these soldiers, and by inference, their ancestors, experienced humiliations that were in no way deserved. Two incidents must be reported if only to demonstrate how far beyond those dark times America has evolved in the 80 years since then:

Despite their heroism and sacrifice, these soldiers, and by inference, their ancestors, experienced humiliations that were in no way deserved. Two incidents must be reported if only to demonstrate how far beyond those dark times America has evolved in the 80 years since then: The 442nd was inactivated in 1946, reactivated in 1947 to the Reserves, and mobilized again in 1968 during the Vietnam War, carrying on the unit’s traditions and honors as the only ground combat unit of the U.S. Army Reserve and headquartered at Fort Shafter, Hawaii with two companies detached in American Samoa. Part of the unit was mobilized for duty during OIF at Balad, Iraq, between 2004-08, receiving the MUC for their actions and losing five more KIA in the ranks. In 2009 it was deployed once more as an element of the 29th Inf Brigade Combat Team to Kuwait, suffering two more losses. During this assignment, several dozen of the unit’s Samoan troops became naturalized U.S. Citizens.

The 442nd was inactivated in 1946, reactivated in 1947 to the Reserves, and mobilized again in 1968 during the Vietnam War, carrying on the unit’s traditions and honors as the only ground combat unit of the U.S. Army Reserve and headquartered at Fort Shafter, Hawaii with two companies detached in American Samoa. Part of the unit was mobilized for duty during OIF at Balad, Iraq, between 2004-08, receiving the MUC for their actions and losing five more KIA in the ranks. In 2009 it was deployed once more as an element of the 29th Inf Brigade Combat Team to Kuwait, suffering two more losses. During this assignment, several dozen of the unit’s Samoan troops became naturalized U.S. Citizens.

The website aims to transform the customer experience for those seeking to sell to or innovate with VA.

The website aims to transform the customer experience for those seeking to sell to or innovate with VA.

U.S. Army Air Corps Bomber Crew

U.S. Army Air Corps Bomber Crew German U-Boat Crew

German U-Boat Crew

President Eisenhower enacted an embargo on Cuba while the CIA began funding Brigade 2506, an armed insurgency group dedicated to overthrowing Castro and reinstating democratic rule in Cuba. By the time the invasion was ready, it consisted of 1,500 exiles. CIA B-26 bombers hit Cuban airfields two days before the invasion. It did not go well for the exiles.

President Eisenhower enacted an embargo on Cuba while the CIA began funding Brigade 2506, an armed insurgency group dedicated to overthrowing Castro and reinstating democratic rule in Cuba. By the time the invasion was ready, it consisted of 1,500 exiles. CIA B-26 bombers hit Cuban airfields two days before the invasion. It did not go well for the exiles. sion came, the Cuban exiles were ambushed by Castro's air forces. They lost five of their 16 bombers on the first day. When they returned to the secret airbase in Nicaragua, Alabama guardsmen repaired, refueled, and rearmed them before they made the six-hour flight back to Cuba. With a manpower shortage in the air, Kennedy finally relented and allowed American pilots to assist.

sion came, the Cuban exiles were ambushed by Castro's air forces. They lost five of their 16 bombers on the first day. When they returned to the secret airbase in Nicaragua, Alabama guardsmen repaired, refueled, and rearmed them before they made the six-hour flight back to Cuba. With a manpower shortage in the air, Kennedy finally relented and allowed American pilots to assist.

Bill: Daily, the memories flood back, often at times when they are least wanted and thus blocking out important relationships, discussions, or, at the very least, quiet times for myself. They are haunting and unwanted, yet they are deeply embedded and so very personal. Because I was there, it really was me. Oh God, what friends I lost and the things I saw and did. I have settled it within myself a thousand times, maybe more, and yet the memories continue. How is it that I was the one to return while so many of my friends did not? Am I blessed or cursed with these memories?

Bill: Daily, the memories flood back, often at times when they are least wanted and thus blocking out important relationships, discussions, or, at the very least, quiet times for myself. They are haunting and unwanted, yet they are deeply embedded and so very personal. Because I was there, it really was me. Oh God, what friends I lost and the things I saw and did. I have settled it within myself a thousand times, maybe more, and yet the memories continue. How is it that I was the one to return while so many of my friends did not? Am I blessed or cursed with these memories?

Thirteen months in Vietnam is a long time for anyone to be deployed. For the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines in 1966, it probably seemed like an eternity. Maj. (ret.) Frank McCarthy's book "Lima-3 and the Mustang Grunt" vividly describes what it was like to fight against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam.

Thirteen months in Vietnam is a long time for anyone to be deployed. For the 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines in 1966, it probably seemed like an eternity. Maj. (ret.) Frank McCarthy's book "Lima-3 and the Mustang Grunt" vividly describes what it was like to fight against the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army along the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Vietnam. "Every time something came up, they said 'send in the 26th Marines," remembered Lee Solomon, a veteran from Lima Company. "We lived in the jungle. We didn't have an area of operations. We were nomads in-country, and everywhere we went, we were in a fight. I spent 19 months in combat there, and that's all I did the whole time."

"Every time something came up, they said 'send in the 26th Marines," remembered Lee Solomon, a veteran from Lima Company. "We lived in the jungle. We didn't have an area of operations. We were nomads in-country, and everywhere we went, we were in a fight. I spent 19 months in combat there, and that's all I did the whole time."