In the Spring of 1814, the war between the British and the still-young United States looked pretty bleak for the Americans. The War of 1812 had started with a bang for the U.S., with American troops crippling the war efforts of Native tribes in the south and making incursions into British Canada in the north.

But 1814 was a turning point for the British Empire. It had just defeated Napoleon and sent the Emperor to exile on the island of Elba. This victory allowed Britain to move 30,000 veteran soldiers from Europe to North America, where a three-pronged plan threatened to cut the new republic to a shell of its former self.

But 1814 was a turning point for the British Empire. It had just defeated Napoleon and sent the Emperor to exile on the island of Elba. This victory allowed Britain to move 30,000 veteran soldiers from Europe to North America, where a three-pronged plan threatened to cut the new republic to a shell of its former self.

The British sent three expeditions, each with 10,000 fresh, skilled soldiers, toward three targets: New York City, Baltimore, and New Orleans. If any of them succeeded in capturing their objectives, the Americans would be forced to make disastrous concessions in the Treaty of Ghent, negotiated to end the war.

If New Orleans fell, it would have invalidated the Louisiana Purchase, which was made by Napoleon and recognized by no one else in Europe. This could have meant the cession of the entire territory to Britain or returning it to Spain. If New York fell, the British would have claimed most of Maine, where the crown established the colony of New Ireland.

At Baltimore, if the defenders of the area could not hold, either of the other two concessions might have been forced on the Americans. All three were the top cities in the United States in terms of size and economic importance.

The British combined forces defeated a naval flotilla of American gunboats and succeeded in landing more than 4,000 troops in Virginia. The British marched into Maryland, routing a small contingent of Americans before meeting a much larger force of U.S. Army Soldiers, Marines, and Sailors at the Battle of Bladensburg.

Despite being outnumbered and assaulting a heavily-defended position, the British won at Bladensburg, from which they marched on Washington and put the capital city to the torch. Their next stop was Baltimore, with a land attack coming from North Point and a naval assault of Fort McHenry, which guarded the entrance to the harbor.

The Americans at Fort McHenry knew the British would be coming for them. The commander of the harbor defenses of Baltimore, Maj. George Armistead wanted the British to know who controlled the point defense of Baltimore Harbor before the attack – and who controlled it when the smoke cleared.

The Americans at Fort McHenry knew the British would be coming for them. The commander of the harbor defenses of Baltimore, Maj. George Armistead wanted the British to know who controlled the point defense of Baltimore Harbor before the attack – and who controlled it when the smoke cleared.

Armistead was a seasoned artillery officer. He cut his teeth in the Quasi-War with France and, earlier in the War of 1812, was part of the force that took the fight to the British in Canada. He had helped the Americans capture Fort George in Ontario and personally delivered the fort's captured flags to President James Madison.

That's how he ended up in command of Fort McHenry. Upon taking command of the fort, he determined that something important was missing from the fort's defenses: a garrison flag. Armistead boldly ordered "a flag so large that the British will have no difficulty seeing it from a distance."

He custom ordered one from local flag maker Mary Pickersgill, who had to sew the massive 30x42-foot Stars and Stripes on the floor of a beer brewery, given its size.  Pickersgill and five associates sewed nonstop for six weeks in preparation for delivery. In August 1813, the flag was delivered to Fort McHenry.

Pickersgill and five associates sewed nonstop for six weeks in preparation for delivery. In August 1813, the flag was delivered to Fort McHenry.

When the battle finally came on Sept. 13, 1814, Armistead and his massive Old Glory were ready. The veteran artillery commander had 1,000 troops under his command, who had spent the past few months reinforcing the bricks and mortars of the fort. He'd even sunk a line of American ships in the harbor to thwart the passage of British warships.

Some 19 British ships shelled Fort McHenry for 25 hours that September with Congreve rockets, cannon shots, and mortars. Since the ships were out of range of Fort McHenry's guns, the fort's defenders hunkered down to wait out the British shelling.

The fort itself, however, was far from bombproof, but Armistead was the only one who knew it. All was almost lost when a British shell hit the magazine, but it failed to explode. Armistead ordered the fort's powder be moved to the rear walls.

Nearly 2,000 shots were fired at the fort. On the morning of Sept. 14, Fort McHenry's defenders hoisted Mrs. Pickersgill's enormous American flag into the sky o ver the area. With its 15 stripes, each two feet wide (the practice of adding stripes for states wasn't stopped until much later), it weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to raise.

ver the area. With its 15 stripes, each two feet wide (the practice of adding stripes for states wasn't stopped until much later), it weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to raise.

With this massive flag flying, there was no doubt the Americans still held the fort. The commander of the British combined force, Vice Admiral Sir Arthur Cochrane, left it to the commander of the British land forces to decide whether or not to attack the fort. Back at North Point, the British had won, but at a cost. They took heavy casualties, including their commander, Maj. Gen. Robert Ross.

With the land forces delayed, their commander mortally wounded, and Americans still in control of Fort McHenry, the British withdrew. The British overland invasion of New York had been turned away at Plattsburgh. The attack on New Orleans in 1815 would also fail, keeping the United States whole through the war's end.

Armistead's flag not only had a major impact on the outcome of the Battle of Baltimore but also touched an individual held aboard one of the British ships in the harbor. Lawyer Francis Scott Key was aboard the HMS Tonnant, negotiating the release of his friend who was being held, prisoner. Knowing the British intent and strength, Key was held aboard this ship throughout the bombing of the fort.

On the Tonnant, he penned a poem, "Defence of Fort M'Henry," which was published in American newspapers the next week. When paired with the tune of the popular drinking song "To Anacreon in Heaven," it became the unofficial anthem of the United States until 1931, when it officially became "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Armistead's original flag is today held by the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where it is occasionally still available for display.

In the summer of 1864, the Confederate States of America was reeling from a series of defeats that would ultimately lead to its demise. Despite the Union victory at Gettysburg in 1863 that turned the Army of Northern Virginia back and the capture of Vicksburg that gave the Union control of the Mississippi River, the outcome of the Civil War was anything but assured.

After leading the Union Army at the Siege of Vicksburg and his subsequent win at Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the Union Armies. With the Confederacy now split in two, Grant took over command of the Army of the Potomac while command of the Western Theater fell to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

After leading the Union Army at the Siege of Vicksburg and his subsequent win at Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the Union Armies. With the Confederacy now split in two, Grant took over command of the Army of the Potomac while command of the Western Theater fell to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

In the spring of 1864, Grant decided to launch simultaneous offensives all along the Confederate lines in an effort to exhaust the Confederacy's resources and its ability to prolong the war. For Sherman, this meant engaging Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston's Army, which protected Atlanta, the south's largest industrial and logistical center.

It was also the largest administrative area for the south, outside of Richmond. While Grant launched his Overland Campaign against the Confederate capital, Sherman headed for Atlanta, where four major railroads connected the Confederacy.

Johnston knew Sherman's relatively massive Army outnumbered him and retreated time and again when Sherman outflanked his defenses. Tired of his retreating, Confederate leaders replaced him with Gen. John Bell Hood, who immediately went on the offensive. At Peach Tree Creek o n Jul. 20, 1864, the Confederates attacked but found Johnston was right. The assault failed, costing Hood casualties he couldn't afford.

n Jul. 20, 1864, the Confederates attacked but found Johnston was right. The assault failed, costing Hood casualties he couldn't afford.

On Jul. 21, Sherman gave Hood one chance to win the battle for Atlanta and perhaps the entire Confederacy. Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson's Army of Tennessee was positioned on the city's outskirts to the east, but his left flank was open while Union cavalry wreaked havoc on the southern railroads.

Hood saw his chance to march a corps of infantry, and Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's cavalry around the Union Army's left flank attacked Sherman's supply line, similar to a move that led to Stonewall Jackson's victory at Chancellorsville, Virginia, earlier in the war.

Wheeler was to attack McPherson's supplies while Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's corps attacked his left rear. It required a 15-mile night march to launch a daring dawn attack. However, the night was hotter than expected, and the Confederate soldiers were exhausted from the maneuver. It wasn't until noon the next day that the rebels were ready to deploy.

Meanwhile, McPherson no ticed his left flank was vulnerable during the night and sent his reserve to defend it. When the rebels launched their “surprise” attack that afternoon, they weren't fighting a baggage train; they were fighting a battle-hardened and fortified infantry.

ticed his left flank was vulnerable during the night and sent his reserve to defend it. When the rebels launched their “surprise” attack that afternoon, they weren't fighting a baggage train; they were fighting a battle-hardened and fortified infantry.

McPherson left Sherman's headquarters and made his way to watch the fighting when he was shot by Confederate infantry under Maj. Gen. Patrick Cleburne. With the General dead, the Confederates began turning the left flank of the Union line and start to overrun it.

More luck for the rebels came in nearby Decatur, where Wheeler's cavalry captured the Fayetteville Road and forced the Union to abandon the town. The fleeing Yankees were barely able to save their supply wagons. But while the initial success was heartening, it soon turned into a disaster for the rebels.

Hardee's infantry on Sherman's left flank may have overrun their enemy at first, but they ran right into infantry and artillery fortified from a nearby hilltop. Unable to dislodge them or advance, Hardee is forced back. Without the infantry's support, Wheeler was forced to abandon Decatur.

The surprise may have failed, but the battle wasn't over. Cheatham's corps attacked the main Union force from the east, centered on nearby Bald Hill. The fighting on Bald Hill was brutal and sometimes hand-to-hand, but Cheatham attacked the Union Army in a series of uncoordinated assaults. The rebels also saw success there, but superior Union artillery and a counter-attack forced them back into the city.

Sherman's Army settled into a siege. After unsuccessfully trying to cut off its supplies for a month using cavalry raids, he cut the railroad lifeline using his entire Army. It forced the Confederates under Hood to abandon Atlanta. The city fell to the Union on Sept. 2, 1864. On Nov. 12, Sherman ordered the city's business district destroyed before departing for his famous “March to the Sea.”

Many civilians will have trouble understanding some facets of military life. The one thing they may never understand is the plethora of ways military personnel can face punishment. Every veteran has a story about either witnessing a bizarre punishment forced upon a troop (or themselves) that seems so outlandish; it's hard to believe - to those who didn't serve, that is.

Troops have been ordered to sweep sunshine off the sidewalks, vacuum the flight line, and pretend to be a ghost; or my personal experience: an Airman trainee was ordered to speak to everyone using sock puppets because he didn't put his dirty socks into a mesh bag.

Troops have been ordered to sweep sunshine off the sidewalks, vacuum the flight line, and pretend to be a ghost; or my personal experience: an Airman trainee was ordered to speak to everyone using sock puppets because he didn't put his dirty socks into a mesh bag.

Not really cruel, but definitely unusual punishment.

Those are just some of the random, uncodified punishment trainees, recruits, and junior enlisted troops have received over the years. There's no book that lists these creative ways to teach junior Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, Marines, and Coast Guardsmen to penalty for not following the rules. They've just been handed down from one generation to another.

There was one method of punishment that sounds like a military urban legend but was actually used for the entire history of the U.S. Navy until 2019: the bread and water punishment. The punishment is just like it sounds: a sailor is confined to the brig for three days with nothing but bread and water.

Confinement on bread and water was one of the Navy's harshest non-judicial punishments and was actually codified as an option to use on E-3 ranks and below for misdemeanor offenses. Like many naval traditions, it was first adopted from the British Royal Navy, but the British discontinued the practice in 1891.

The United States continued using bread and water confinement because it was a more humane way to quickly punish sailors at sea than flogging, which the U.S. Navy discontinued in 1862.

The United States continued using bread and water confinement because it was a more humane way to quickly punish sailors at sea than flogging, which the U.S. Navy discontinued in 1862.

In the years that followed, confinement on "minimal rations" was allowed for up to 30 days. In 1909, it was reduced to seven days. By 2019, it was just three - but you got as much bread and water as you wanted.

For the junior enlisted who faced this punishment, it might have seemed draconian, but it was supposed to save them from a greater punishment, one that might lead them to a court-martial or discharge, especially if the evidence against them is overwhelming.

One U.S. Navy Captain's overuse of the punishment led to his ship being dubbed "the USS Bread and Water," a Navy review, and the eventual discontinuation of the practice. On January 1, 2019, changes to the Uniformed Code of Military Justice were implemented that did not include bread and water.

By Kevin A. Konczak

By 1962 the world was becoming a very scary place punctuated by continuing confrontations between global communist and democratic powers, alongside growing civil, racial, and political unrest. In Southeast Asia, the Korean War brought an indecisive outcome, and the tide of combat in Vietnam now favored communist forces despite US advisors in place since 1956. Further, in 1961 alone, there was an armed conflict between communist and democratic armies along the Chinese-Burma border, UN peacekeeping forces fighting at Kabalo and Katanga (Operation Rampunch) in the Congo, and the US-backed Bay of Pigs, a failed attempt to overthrow Castro's regime in  Cuba. In Europe, the Berlin Wall was constructed following decades-long Soviet blockades leading to the activation of more than 150,000 US guardsmen and reservists together with Operation Stair Step, the largest jet deployment in history. Then in October 1962, provoked by ongoing US efforts against Cuba (Operation Mongoose), the world held its breath as nuclear war was wagered during the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Growing complexity on the world stage, in combination with civil rights reformation, made timely and accurate intelligence at the highest levels of government indispensable. So, in 1962 President Kennedy authorized the formation of an elite special-ops unit, liberated from red tape and able to deploy at a moment's notice. A unit that did not need to wait for orders to mobilize and arrived armed with state-of-the-art equipment to carry out their mission. Christened DASPO, Department of the Army Special Photographic Office, the corps was a Special Forces unit of sorts but comprised of combat photographers.

Cuba. In Europe, the Berlin Wall was constructed following decades-long Soviet blockades leading to the activation of more than 150,000 US guardsmen and reservists together with Operation Stair Step, the largest jet deployment in history. Then in October 1962, provoked by ongoing US efforts against Cuba (Operation Mongoose), the world held its breath as nuclear war was wagered during the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Growing complexity on the world stage, in combination with civil rights reformation, made timely and accurate intelligence at the highest levels of government indispensable. So, in 1962 President Kennedy authorized the formation of an elite special-ops unit, liberated from red tape and able to deploy at a moment's notice. A unit that did not need to wait for orders to mobilize and arrived armed with state-of-the-art equipment to carry out their mission. Christened DASPO, Department of the Army Special Photographic Office, the corps was a Special Forces unit of sorts but comprised of combat photographers.

The Pentagon charged Major Arthur A. Jones with designing and organizing a brand-new command to provide state-of-the-art photographs and film to the Joint Chiefs, the Pentagon staff, and the United States Congress. First headquartered at the Army Pictorial Center on the former Paramount Pictures lot in Queens, New York, the staff later moved to the US Army Photographic Agency at the Pentagon. To meet the demand for global coverage, DASPO was comprised of three sections: DASPO CONUS (Continental United States), DASPO Panama, and DASPO Pacific. Photographers were free to operate with nearly unlimited access and took their orders directly from the Army Chief of Staff, General Decker. Decker's very specific demands of DASPO included a full-time Rapid Response Team, highly mobile and unencumbered, with every member issued a top-secret clearance and the best equipment. The officers assigned to the unit coordinated activities while enlisted personnel served on the front lines to provide the photography.

The unit was populated by cherry-picking the best of the best from the staff at the Army Pictorial Center and students from the Army Signal School at Fort Monmouth, while staff began to fill the ranks of command positions with sound specialists, motion picture cameramen, and still photographers. Meanwhile, Jones (now a Lieutenant Colonel) and his staff kept a vigil for draftees with backgrounds that matched the unit's mission. Comprised of lifers and green recruits, enlistees, and draftees, it would seem the only thing DASPO personnel had in common was that they had little in common, as few men followed the same path to the unit. When asked how he was selected for DASPO, retired Hollywood cameraman Stewart Barbee, who served as a DASPO motion picture cameraman from 1969-70, swears, "I still don't know." On the other hand, veteran photographer Peter "Rupy" Ruplenas had seen combat as a Signal Corps photographer in World War II and the Korean War before volunteering to DASPO in 1966.

The unit was populated by cherry-picking the best of the best from the staff at the Army Pictorial Center and students from the Army Signal School at Fort Monmouth, while staff began to fill the ranks of command positions with sound specialists, motion picture cameramen, and still photographers. Meanwhile, Jones (now a Lieutenant Colonel) and his staff kept a vigil for draftees with backgrounds that matched the unit's mission. Comprised of lifers and green recruits, enlistees, and draftees, it would seem the only thing DASPO personnel had in common was that they had little in common, as few men followed the same path to the unit. When asked how he was selected for DASPO, retired Hollywood cameraman Stewart Barbee, who served as a DASPO motion picture cameraman from 1969-70, swears, "I still don't know." On the other hand, veteran photographer Peter "Rupy" Ruplenas had seen combat as a Signal Corps photographer in World War II and the Korean War before volunteering to DASPO in 1966.

The three branches of DASPO operated similar to one another, with geographic responsibility the distinguishing difference. Headed by SFC Jack Yamuguchi, DASPO CONUS (Continental United States) was based in the United States, but unlike DASPO Pacific and DASPO Panama, DASPO CONUS was capable of being sent anywhere in the world. In one example, President Johnson sent troops to the Dominican Republic in 1965 to secure the peace after civil unrest broke out. When the Pentagon lost contact with the DASPO Panama detachment, a team from DASPO CONUS was dispatched to cover the rebel invasion. Coming under direct fire, the men were able to disguise themselves and complete the mission, filming the rebel's strength, combat positions, and equipment to earn the Combat Army Commendation Medal. The Panama Detachment, the smallest of the three DASPO entities, totaled eight photographers and was based at Fort Clayton in the Panama Canal Zone, documenting US training inside the Canal Zone, natural disasters, and political developments in Central and South America.

By far and away, the Pacific Detachment of DASPO, nicknamed "Team Charlie," was the most active of the DASPO sections due to its coverage of Vietnam combat operations. Based in Fort Shafter, Hawaii, DASPO Pacific sent rotating teams of photographers into Vietnam for three-month tours of duty, in contrast with conventional combat photography units whose personnel served standard one-year deployments in-country and covered only their unit's activities. Teams usually consisted of a commanding officer, a non-commissioned officer, and between ten to eighteen enlisted sound specialists, motion picture cameramen, and still photographers. Although other military departments and press organizations sent their own photographers into the war zones, DASPO was considered "the Army's elite photographic unit" with unprecedented access to the action.

Team Charlie operated out of a rented three-story gated house in Saigon, only minutes from the Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Dubbed "The Villa," this compound served as both office and barracks from which two and three-person teams would rotate into the field. DASPO photographers followed combat units into every type of terrain in Vietnam; jungles, Highlands, urban settings, swamps, and rice paddies, … capturing the war from a soldier's view and putting themselves at personal risk, suffering the same hardships. Documenting the action at Khe Sanh, Dak To, the La Drang Valley, and countless other operations, photographers would become part of the unit they were covering, enduring what the unit endured, and staying with it until the mission ended or they ran out of film. In one case, Spc. 5 Theodore "Ted" Acheson arrived in Vietnam in February 1968, just days after the Tet Offensive began, and was wounded during a firefight near the city of Hue. Later, during a firefight near La Chu, Acheson filmed a squad of Soldiers destroying a series of enemy bunkers, again exposing himself to hostile fire and shooting one of the only films documenting actions that resulted in a soldier receiving the Medal of Honor, Spc. 4 Robert Patterson. "The film also shows other acts of valor that resulted in two Silver Stars and five Bronze Star medals," Acheson noted.

Team Charlie operated out of a rented three-story gated house in Saigon, only minutes from the Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Dubbed "The Villa," this compound served as both office and barracks from which two and three-person teams would rotate into the field. DASPO photographers followed combat units into every type of terrain in Vietnam; jungles, Highlands, urban settings, swamps, and rice paddies, … capturing the war from a soldier's view and putting themselves at personal risk, suffering the same hardships. Documenting the action at Khe Sanh, Dak To, the La Drang Valley, and countless other operations, photographers would become part of the unit they were covering, enduring what the unit endured, and staying with it until the mission ended or they ran out of film. In one case, Spc. 5 Theodore "Ted" Acheson arrived in Vietnam in February 1968, just days after the Tet Offensive began, and was wounded during a firefight near the city of Hue. Later, during a firefight near La Chu, Acheson filmed a squad of Soldiers destroying a series of enemy bunkers, again exposing himself to hostile fire and shooting one of the only films documenting actions that resulted in a soldier receiving the Medal of Honor, Spc. 4 Robert Patterson. "The film also shows other acts of valor that resulted in two Silver Stars and five Bronze Star medals," Acheson noted.

The primary purpose of DASPO was to inform the Pentagon and the Department of the Army, but their iconic photos and film often accompanied news reports and fed daily television coverage for consumption by the American public, bringing the realities of the Vietnam war into millions of homes. Much of the material they shot was classified at the time and intended either for analysis or use in combat training, but approximately twenty-five percent of their material was made available for publication during and after the war. According to Captain William D. San Hamel, "the Soldiers of DASPO never knew where their products might show up and are still surprised today to suddenly see their work appear. The Army would actually hold auctions where the news media would bid on the photos and footage", he said.

The photographs and film captured by DASPO document the Vietnam War and are now historical artifacts of this period. After the war, DASPO members established the DASPO Archive and a scholarship fund at Texas Tech University. The scholarship funds the preservation of images and audio recordings in the names of Kermit H. Yoho and Charles "Rick" F. Rein, DASPO members who were killed in action in Vietnam. Specialist Yoho was killed on February 10, 1966, when he was hit by an exploding grenade only seven days before returning to Hawaii following his last 90-day assignment in Vietnam. Sargent Rein was shot down in November 1968 by hostile enemy action while flying over the Kontum province.

The photographs and film captured by DASPO document the Vietnam War and are now historical artifacts of this period. After the war, DASPO members established the DASPO Archive and a scholarship fund at Texas Tech University. The scholarship funds the preservation of images and audio recordings in the names of Kermit H. Yoho and Charles "Rick" F. Rein, DASPO members who were killed in action in Vietnam. Specialist Yoho was killed on February 10, 1966, when he was hit by an exploding grenade only seven days before returning to Hawaii following his last 90-day assignment in Vietnam. Sargent Rein was shot down in November 1968 by hostile enemy action while flying over the Kontum province.

On March 29, 1973, the last US combat troops left Vietnam following the signing of a peace agreement in Paris and ending over ten years of US intervention. Likewise, the government draft was ended in favor of a volunteer military, and the country began a widespread postwar downsizing. DASPO Pacific was closed in December of 1974, with the remaining personnel and equipment transferred to DASPO CONUS. Eventually, all three DASPO detachments were consolidated and renamed the Army Special Operations Pictorial  Detachment at Fort Bragg. Today the Army's 55th Combat Camera Company at Fort Meade carries out the mission that began with the formation of DASPO in 1962.

Detachment at Fort Bragg. Today the Army's 55th Combat Camera Company at Fort Meade carries out the mission that began with the formation of DASPO in 1962.

During its thirteen-year history, approximately 325 persons served in roles with DASPO, 200 of them as soldier photographers. Not surprisingly, most continued on to prestigious careers in military and civilian life as photojournalists, advertising executives, Smithsonian and National Geographic photographers, Hollywood special effects cameramen, and news correspondents. The extraordinary images DASPO photographers captured will live as historical artifacts, a permanent and powerful record of the war and global events during an uncertain and highly controversial time, preserved for future generations.

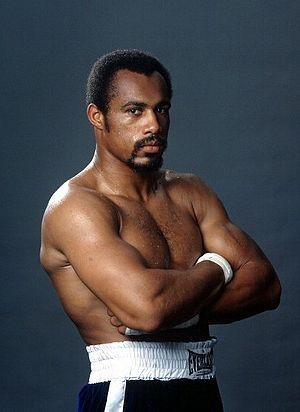

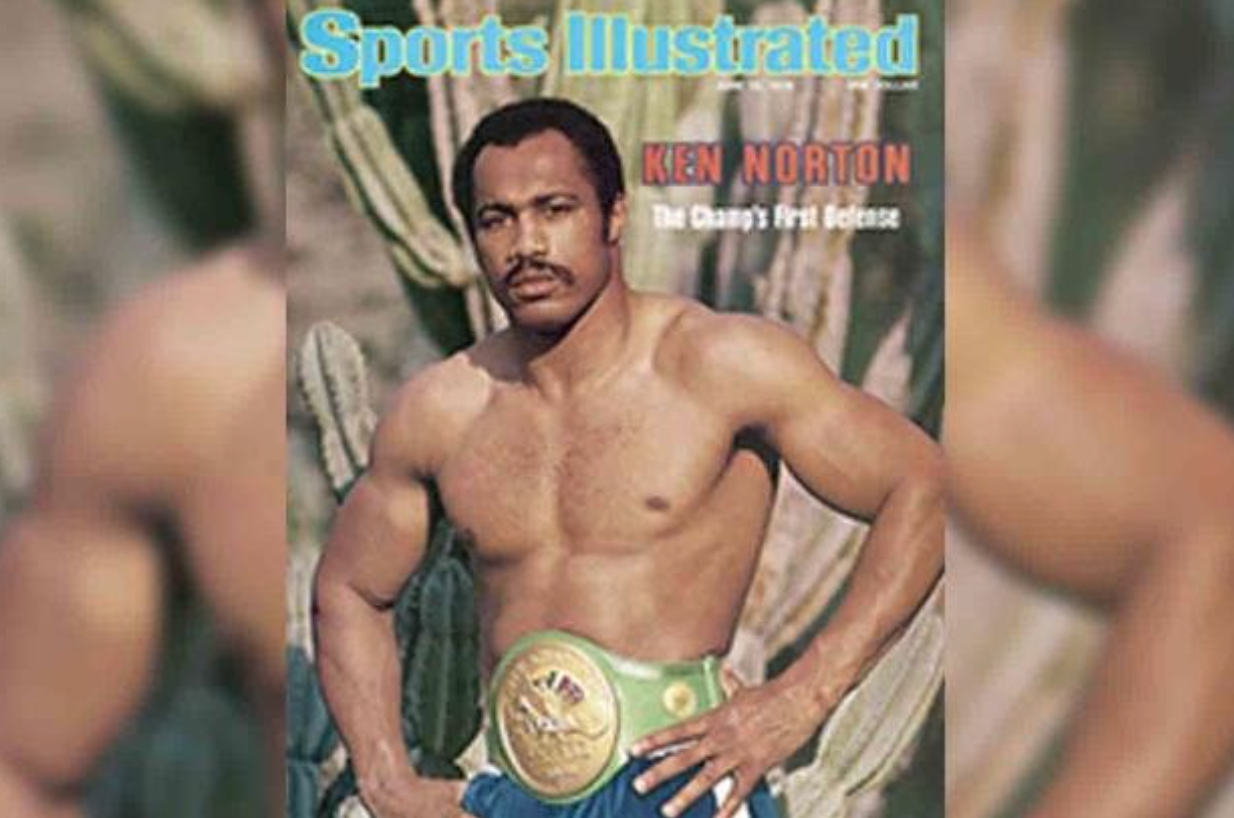

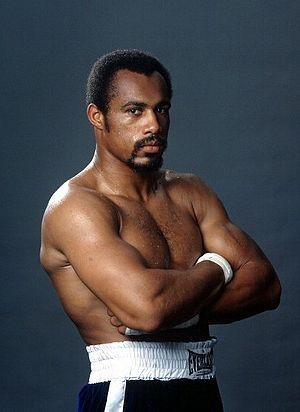

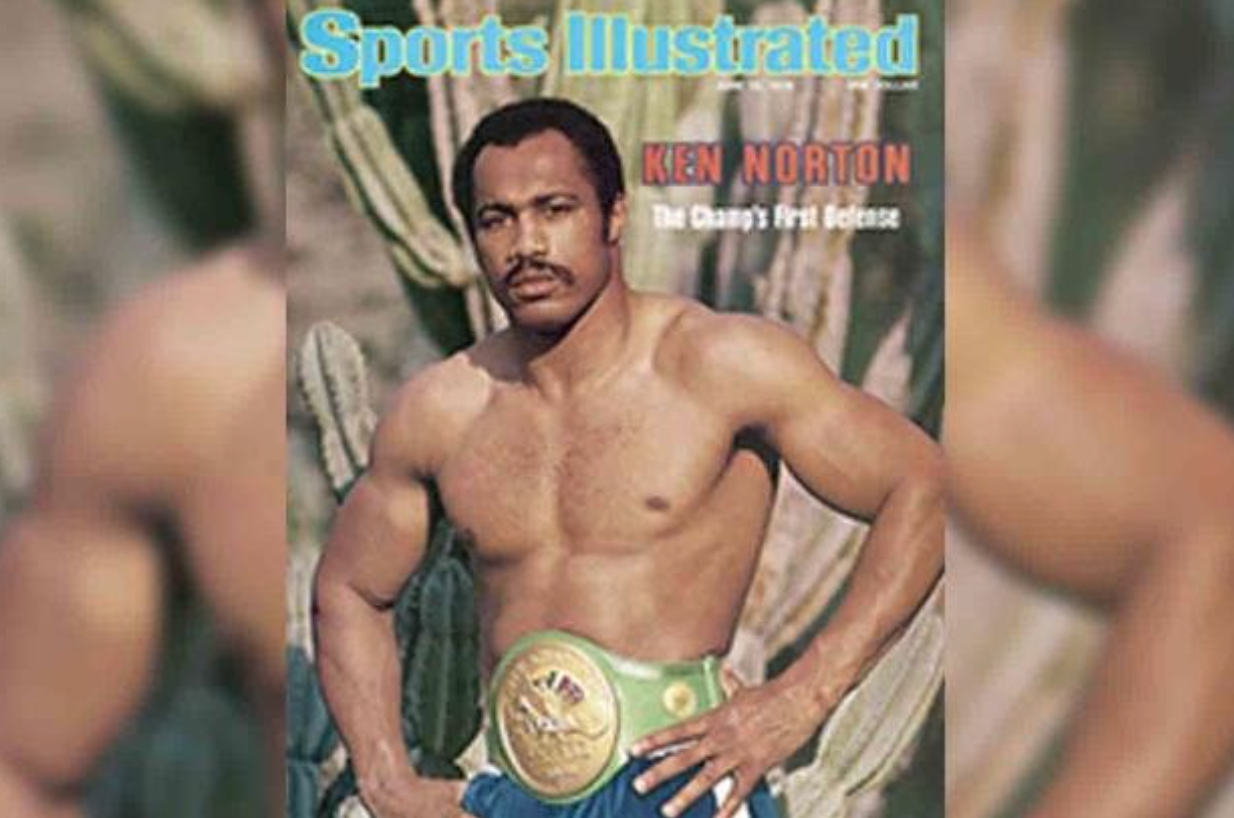

In March 1964, boxer Cassius Clay announced his conversion to Islam and changed his name to Muhammad Ali after his famous defeat of Sonny Liston. At the same time, Ken Norton was in the Marine Corps, learning the ropes of a sport he came to love: boxing.

Norton was a high-performing athlete his entire life, excelling at track and field and football, among others. Boxing was no different. While serving as a signals intelligence Marine, he would rack up a 24-2 record, making him one of the best fighters to come out of the Marine Corps.

Norton was a high-performing athlete his entire life, excelling at track and field and football, among others. Boxing was no different. While serving as a signals intelligence Marine, he would rack up a 24-2 record, making him one of the best fighters to come out of the Marine Corps.

By the end of his boxing career, he boasted a 42-7-1 record with 33 knockouts. In a career that included knocking out undefeated Duane Bobick in 58 seconds at Madison Square Garden, sharing a ring with George Foreman, and being named one of Ring Magazine's 50 Greatest Heavyweights, his most memorable moment came in 1973, when he delivered Muhammad Ali's second loss ever.

"I was concentrating so hard on trying to beat Norton that I was unaware of the pain. He was better than I thought," Ali would say of Norton.

Ali had famously refused to be drafted into the U.S. Army in 1967 and was convicted of violating the Selective Service Act. His boxing license was suspended, and he was stripped of the heavyweight title. The Supreme Court overturned the conviction, and by 1970, Ali was back in the ring.

Meanwhile, Norton was considered an up-and-comer, fighting other up-and-comers, most of them relatively unknown fighters. He was boxing legend Joe Frazier's sparring partner for a time and had the same trainer.

Norton fought Henry Clark during an Ali undercard match in 1972. Clark had an impressive record of his own, along with some high-profile opponents, including Liston. Norton beat Clark in that match, his most high-profile win to that date, which put him on Ali's radar.

Ali's comeback tour hit a speedbump in 1971 in the "Fight of the Century," when he was set to challenge heavyweight champion, Joe Frazier at Madison Square Garden.

The much-publicized fight was everything it was billed to be, with Ali's trademark smack talk building the fight up and 15 rounds of two undefeated boxers giving it their best. Though Frazier handed Ali his first professional loss, Ali was far from done.

Norton, meanwhile, was less flashy but putting in the work all the same. Unless you were drawing thousands of people like Ali and Frazier, boxing didn't always pay well. Norton once quipped that a hot dog would be a gourmet meal for him and his son at this point in his career. But by the time he stepped into the ring with Ali, Norton was the sixth-ranked contender in the world.

Norton, meanwhile, was less flashy but putting in the work all the same. Unless you were drawing thousands of people like Ali and Frazier, boxing didn't always pay well. Norton once quipped that a hot dog would be a gourmet meal for him and his son at this point in his career. But by the time he stepped into the ring with Ali, Norton was the sixth-ranked contender in the world.

Despite this ranking, Ali didn't appear to take the Marine Corps veteran seriously. In 1973, the year of his first fight with Ali, Norton turned 30 years old and was still a relatively unknown "ham-and-egger" - boxing slang for a fighter who doesn't have much fight in him. He had never beaten a Top 10 opponent and was entering the ring with an already-recognized boxing legend, even by Norton himself.

"The first time I fought Ali, I felt it was an honor just to be in the same ring as him," Norton later said.

Norton was physically ready for what was going to be the biggest fight of his career until that point. He was at the peak of fitness. His mental state was something else. Ali's signature pre-fight trash talk took its toll on Norton. He was called "Ken Somebody" by Sports Illustrated, and sportscaster Howard Cosell called him a "tailor-made" fall guy for Ali's climb back to the championship.

Ali's "easy target" was more than just physically prepared; he was mentally ready, too. He'd read a copy of "Think and Grow Rich" by Napoleon Hill, a book he would credit with changing his life forever. In Norton's mind, he could beat Ali, even if no one else thought so.

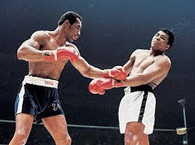

On March 31, 1973, Ken Norton returned to San Diego, where he'd first learned to box, to fight "The Greatest," Muhammad Ali. No one expected Norton to win the fight at the San Diego Sports Arena that night, and Ali was favored at 1-5 odds. Norton was about to turn into a boxing legend in his own right.

On March 31, 1973, Ken Norton returned to San Diego, where he'd first learned to box, to fight "The Greatest," Muhammad Ali. No one expected Norton to win the fight at the San Diego Sports Arena that night, and Ali was favored at 1-5 odds. Norton was about to turn into a boxing legend in his own right.

When the bell rang, Norton went on the offensive. His unorthodox fighting style made it difficult for Ali to time his movements or defend Norton's jabs. Throughout 12 rounds, Norton took the fight to Ali, silencing "The Greatest" for the first time ever after breaking Ali's jaw in the ring.

Many believe it was the second round. Ali and his trainer say it was in the first round. Norton believes it happened in the 11th round. No matter when it happened, Ali's mouth filled with blood, and he was on the defensive against Norton for most of the fight. When the final bell rang, Norton was declared the winner in a split decision.

Norton's previous fight earned him a $300 purse. He received $50,000 for beating Ali. The two soon agreed to meet again, this time in Inglewood, California. Ali would prepare for the next fight with more determination.

"I only look at this as a spanking," Ali told Johnny Carson on "The Tonight Show" weeks after the fight. "This will make me be more serious, train harder and not take people for granted. ... Norton better watch out because musically speaking, if he doesn't see sharp, he's gonna be flat."

Norton would fight Ali a total of three times, with the third coming at Yankee Stadium in New York in 1976. The second fight was a close split decision the judges handed to Ali. The third match was also a close call given to Ali, but it was the one that most people watching (and Ali himself) believed that Norton actually won.

Norton would fight Ali a total of three times, with the third coming at Yankee Stadium in New York in 1976. The second fight was a close split decision the judges handed to Ali. The third match was also a close call given to Ali, but it was the one that most people watching (and Ali himself) believed that Norton actually won.

"Kenny's style is too difficult for me," Ali later said. "I can't beat him, and I sure don't want to fight him again. I honestly thought he beat me in Yankee Stadium, but the judges gave it to me, and I'm grateful to them."

Norton thought he was robbed of the win, too. Despite the two losses to Ali, his career was forever changed. He would fight until 1981, stepping into the ring with the likes of Foreman and Gerry Cooney. The Ring magazine would remember him as one of the 50 Greatest Heavyweights of All Time.

Before his death in 2013, Norton would be inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame, the International Boxing Hall of Fame, the United States Marine Corps Sports Hall of Fame, and the World Boxing Council Hall of Fame.

The names Pete Mitchell and Nick Bradshaw might mean very little to most, but when these two are called by their aviator call signs "Maverick" and "Goose," that all changes even though they're the same characters.

The names Pete Mitchell and Nick Bradshaw might mean very little to most, but when these two are called by their aviator call signs "Maverick" and "Goose," that all changes even though they're the same characters.

That's the nature of military call signs. They're like an inverted secret identity.

Not all call signs are as cool as "Toro," "Elvis," or "Yoda," all real-world call signs. Many are meant to "build a humility-based culture," which is officer milspeak for "constantly reminding pilots of their most embarrassing moments."

For every pilot flying an aircraft in the military, there is a story behind their call sign that they probably wouldn't want to share with their mother. As far as military traditions go, call signs are not just one of the more useful (in terms of radio communication); they also have the most personality.

Since the earliest days of aviation, both ground controllers and other pilots needed the means to identify other aircraft and pilots. Though not specifically called "call signs" from the start, they were an important way to communicate while confusing the enemy. Using nicknames instead of a pilot's name was easier and protected their identities.

By World War II, the use of call signs grew in popularity. Pilots and other aviation officers had names based on their appearance, personality, background, or some pop-culture reference. One of the best examples from this era is Marine Corps Col.Gregory Boyington, whose call sign references his age compared to the rest of his pilots.

By World War II, the use of call signs grew in popularity. Pilots and other aviation officers had names based on their appearance, personality, background, or some pop-culture reference. One of the best examples from this era is Marine Corps Col.Gregory Boyington, whose call sign references his age compared to the rest of his pilots.

Rather than his real first name, Boyington is better recognized in history by his call sign: "Pappy."

The popularity of using call signs only increased during the Vietnam War, and by the 1980s, it became an institution. Today, getting a call sign is a rite of passage.

Pilots and naval aviators do not get to pick their own call signs. If they did, they would probably sound more like the X-Men or the American Gladiators going into combat than anything else. There would be a Royal Rumble over who gets to be "Maverick" or "Iceman."

Instead, most are bestowed with their new alter ego when they get to their first operational squadron as a junior officer. During this time spent with their new unit, things happen,  stories are told, and ideas are tossed around. Within about a year or so, the worst possible outcome happens when their co-workers take a vote on what to call the new guy or gal.

stories are told, and ideas are tossed around. Within about a year or so, the worst possible outcome happens when their co-workers take a vote on what to call the new guy or gal.

The squadron commander gets the final say, but that's not likely to save any embarrassment. Once the call sign is in place, it's unlikely ever to change. Air Force tradition holds that once a pilot flies a combat sortie with their call sign, it can never change. So embracing the new moniker is important because you're gonna hear it a lot.

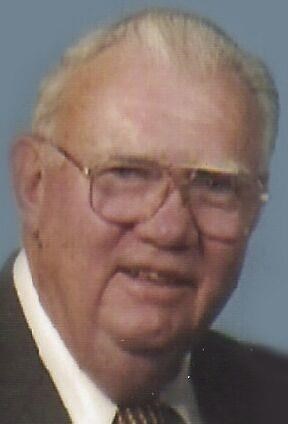

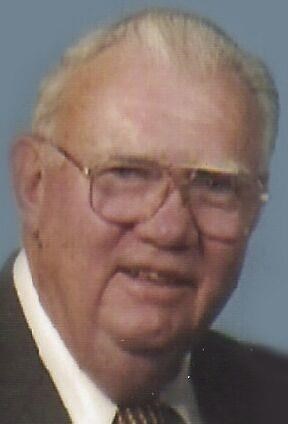

Lessons From a Life In Uniform By Buck Cole

Every veteran has a unique and interesting story to tell. Many of us are plucked out of our lives in the United States and sent to join our chosen branch of service, where we often travel around the country and around the world, engaging our senses in a series of new experiences. Air Force veteran Buck Cole is one of us.

Every veteran has a unique and interesting story to tell. Many of us are plucked out of our lives in the United States and sent to join our chosen branch of service, where we often travel around the country and around the world, engaging our senses in a series of new experiences. Air Force veteran Buck Cole is one of us.

Cole is not only a veteran; he's a retired history teacher, which gives him a unique perspective on what to teach us about the lessons he's learned and - more importantly - how to go about teaching us.

As a veteran who served during the Cold War, he will tell you he was never stationed in a war zone and his only taste of combat came in the form of a bar fight with a sailor in the Philippines. One day, Cole watched a retired Army colonel give a Veterans Day speech to a group of middle schoolers. The colonel spoke in grand "platitudes" about moral conduct, sacrifice, and honor.

A great concept for a Veterans Day speech, Cole thought, but not something that would engage younger generations or their interest in military life and service. Instead of doing something similar, Cole told a story about how he and his barracks bunkmate almost set their building on fire while cooking rice. It wasn't a grand story, but it was an authentic and fun story about military life.

Cole began to think about all the great stories he'd accumulated during his 11 years of service. From leaving his home in Texas and traveling to the Philippines, Europe, and back to the States over the course of his career, he'd garnered many. He set out to retell them in a way that avoided the feel of a Hallmark greeting card.

His stories begin in Waco, Texas, where he grew up in the 1960s and decided to join the U.S. Air Force during the height of the Vietnam War. Younger veterans will relish his descriptions of what it was like to make the transit to basic training at the time.

His stories begin in Waco, Texas, where he grew up in the 1960s and decided to join the U.S. Air Force during the height of the Vietnam War. Younger veterans will relish his descriptions of what it was like to make the transit to basic training at the time.

Air Force veterans will recall their own first experience at Lackland and how some things don't change - like "rainbow flights," "dorm chiefs," and "Dear John" letters. The book is also full of memories from bases long gone, like those of Chanute and Clark Air Force Bases.

Each story is packed with nostalgia, reflections, and lessons learned that anyone with even a cursory interest in history or military service will have trouble putting down. It quickly becomes apparent that so many of us share the same thoughts, whether we joined in the 60s, 80s, or 2000s.

"Blue Boy: Lessons From a Life In Uniform" is his collection of stories and life lessons from Buck Cole's Air Force career. Some 42 years after leaving the service, he published the book in 2022. The journey of writing a book turned out to be a lesson in and of itself, as he struggled to check his facts and choose which stories to tell. His lesson: Don't wait 50 years to write your own story.

By Joseph Newkirk

As United Nations representatives and leaders from North Korea signed a ceasefire agreement to end the Korean War on July 27, 1953, a lone bugler played taps at 2400 hours (midnight) at the UN Truce Camp in Panmunjom, Korea. United States Marine Sgt. Bob Ericson, a native of Quincy, became known forever after as the war's "ceasefire bugler."

Ericson had been playing the bugle since age 11 when he joined the Drum and Bugle Corps of Quincy's American Legion Post 37. This fortuitous association placed him among young men of the nation's best-drilled Corps. In 1946, the Quincy Corps, with young Ericson on the bugle, won the national championship in San Francisco.

Ericson had been playing the bugle since age 11 when he joined the Drum and Bugle Corps of Quincy's American Legion Post 37. This fortuitous association placed him among young men of the nation's best-drilled Corps. In 1946, the Quincy Corps, with young Ericson on the bugle, won the national championship in San Francisco.

A year earlier, during a workforce shortage caused by World War II, Ericson had detasselled corn alongside German POWs held at Camp Ellis near Macomb. After joining the Marines in 1950 and completing basic training at Camp Lejeune, N.C., the Corps named him 1st Service Battalion Bugler of the 1st Marine Division. The war in Korea loomed over the horizon.

In 1948, Korea had been divided at the 38th parallel with a communist government in the north and the People's Republic in the south. On June 25, 1950, North Korea invaded its southern neighbor, and President Harry Truman, without waiting for congressional approval, deployed American troops.

Fought by U. S. and UN Forces to stop the spread of communism in Southeast Asia, the war cost 5 million military and civilian lives, with about 40,000 Americans killed and 100,000 wounded. The war ended in a stalemate, and Korea remains divided to this day. Peace negotiations began soon after the war started in 1951, but politics as mean and vicious as the fighting held them up for two years.

In a 2010 interview, Ericson reflected on this dismal interlude: "Negotiations took place in a tent and were made difficult by the Koreans, who cut legs off the chairs to sit taller than UN representatives. They also cut the bases off the American flags. During this two-year charade, most of the causalities and fatalities of the war took place. South Korean President Syngman Rhee tried to destroy the ceasefire by releasing 20,000 North Korean POWs, but they were so tired of war they disappeared into the population rather than fight."

After officials signed the truce, an exchange of sick and wounded prisoners took place with the Koreans. The Marines assigned Ericson to Freedom Village - where doctors and nurses received weakened soldiers - and there, he played daily bugle calls for the camp.

Governments around the world remembered and honored Sgt. Ericson's efforts. In 1985, President Reagan appointed him to the commission, which was to design, build and dedicate the National Korean War Memorial on the Mall in Washington, D. C. He was named the official bugler at the dedication ceremony. Ericson and his wife, Gladys, with a contingent of 20 local Korean War veterans, took a train to Washington for the ceremony, where about 200,000 veterans had gathered. During the practice session for the program, a spotlight shone on Ericson as he played taps and then held the last note until fading into the orchestra's rendition of "America the Beautiful." He gradually muted his bugle and waited for the song to begin, but as he looked down for a cue from the orchestra, the musicians gave him a standing ovation.

In 2003, the Korean government invited Ericson to play at the 50th anniversary of the war's ceasefire. During this time, the Norwegian Embassy learned about the "ceasefire bugler" and invited him to play in that country. In Norway, after a limousine ride to the Norwegian War Memorial courtesy of the government, a national magazine featured his performance and a half-page photograph.

Ericson also played his bugle at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery in Washington, the dedication of the Illinois Korean War Memorial at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, the Korean War Memorial at the Illinois Veterans Home in Quincy, the burial of the last known Civil War veteran in Memphis, Mo., and several international memorial programs. He became director of the same Quincy American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps he had played in as a youth and served as an officer in the Marine Corps League and the Korean War Veterans.

Robert "Bob" Ericson was born on August 22, 1930, and except for three years in the USMC, he lived in Quincy his entire life. His father was a World War I veteran who later became a postal worker. In 1948, Ericson married Gladys Holtschlag and, after his discharge on January 4, 1954, accepted a job offer from his father-in-law, the owner of Holtschlag Florist. For the first eight years of his 35-year career, he worked in the greenhouse as a grower, learning this trade on the job and by using the G.I. Bill for specialized horticultural training. He then became a floral designer, and in 1969 the National FTD named him Designer of the Year.

Robert "Bob" Ericson was born on August 22, 1930, and except for three years in the USMC, he lived in Quincy his entire life. His father was a World War I veteran who later became a postal worker. In 1948, Ericson married Gladys Holtschlag and, after his discharge on January 4, 1954, accepted a job offer from his father-in-law, the owner of Holtschlag Florist. For the first eight years of his 35-year career, he worked in the greenhouse as a grower, learning this trade on the job and by using the G.I. Bill for specialized horticultural training. He then became a floral designer, and in 1969 the National FTD named him Designer of the Year.

After contracting rheumatoid arthritis, Ericson reached a point in 1989 when he could no longer stand for long periods of time and accepted a job as the first Veterans Service Officer for the Illinois Disabled Veterans of America at the Illinois Veterans Home in Quincy. In that position, he helped former servicemen and women receive benefits and medical aid and directed them to VA programs and agencies.

Ericson lived at the Veterans Home himself until his death on July 13, 2021. He had come full circle: his first public bugle performance took place in the Home's Lippincott Hall on Armistice Day (now Veterans Day) of 1941, twenty-six days before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that began U. S. involvement in World War II.

Ericson's most poignant performances, though, were perhaps private. He played taps for 69 years at nearly 7,000 funerals of American military veterans who solemnly entered the hereafter on the notes of a lone Marine bugler bestowing a final elegy from a grateful nation.

Bob Ericson passed away on July 13, 2021. His obituary stated, "Burial: Calvary Cemetery, Quincy, Illinois with full military honors by American Legion Post 37 and the United States Marine Corps Funeral Honors Detail.

Being a life-long florist, Bob would appreciate floral tributes. Memorial may be made to the Illinois Veterans Home Activities Fund or Camp Callahan. "

But 1814 was a turning point for the British Empire. It had just defeated Napoleon and sent the Emperor to exile on the island of Elba. This victory allowed Britain to move 30,000 veteran soldiers from Europe to North America, where a three-pronged plan threatened to cut the new republic to a shell of its former self.

But 1814 was a turning point for the British Empire. It had just defeated Napoleon and sent the Emperor to exile on the island of Elba. This victory allowed Britain to move 30,000 veteran soldiers from Europe to North America, where a three-pronged plan threatened to cut the new republic to a shell of its former self.  The Americans at Fort McHenry knew the British would be coming for them. The commander of the harbor defenses of Baltimore, Maj. George Armistead wanted the British to know who controlled the point defense of Baltimore Harbor before the attack – and who controlled it when the smoke cleared.

The Americans at Fort McHenry knew the British would be coming for them. The commander of the harbor defenses of Baltimore, Maj. George Armistead wanted the British to know who controlled the point defense of Baltimore Harbor before the attack – and who controlled it when the smoke cleared.  Pickersgill and five associates sewed nonstop for six weeks in preparation for delivery. In August 1813, the flag was delivered to Fort McHenry.

Pickersgill and five associates sewed nonstop for six weeks in preparation for delivery. In August 1813, the flag was delivered to Fort McHenry. ver the area. With its 15 stripes, each two feet wide (the practice of adding stripes for states wasn't stopped until much later), it weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to raise.

ver the area. With its 15 stripes, each two feet wide (the practice of adding stripes for states wasn't stopped until much later), it weighed 50 pounds and required 11 men to raise.

After leading the Union Army at the Siege of Vicksburg and his subsequent win at Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the Union Armies. With the Confederacy now split in two, Grant took over command of the Army of the Potomac while command of the Western Theater fell to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

After leading the Union Army at the Siege of Vicksburg and his subsequent win at Chattanooga, Ulysses S. Grant was promoted to Lieutenant General and given overall command of the Union Armies. With the Confederacy now split in two, Grant took over command of the Army of the Potomac while command of the Western Theater fell to Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.  n Jul. 20, 1864, the Confederates attacked but found Johnston was right. The assault failed, costing Hood casualties he couldn't afford.

n Jul. 20, 1864, the Confederates attacked but found Johnston was right. The assault failed, costing Hood casualties he couldn't afford. ticed his left flank was vulnerable during the night and sent his reserve to defend it. When the rebels launched their “surprise” attack that afternoon, they weren't fighting a baggage train; they were fighting a battle-hardened and fortified infantry.

ticed his left flank was vulnerable during the night and sent his reserve to defend it. When the rebels launched their “surprise” attack that afternoon, they weren't fighting a baggage train; they were fighting a battle-hardened and fortified infantry.

Troops have been ordered to sweep sunshine off the sidewalks, vacuum the flight line, and pretend to be a ghost; or my personal experience: an Airman trainee was ordered to speak to everyone using sock puppets because he didn't put his dirty socks into a mesh bag.

Troops have been ordered to sweep sunshine off the sidewalks, vacuum the flight line, and pretend to be a ghost; or my personal experience: an Airman trainee was ordered to speak to everyone using sock puppets because he didn't put his dirty socks into a mesh bag.  The United States continued using bread and water confinement because it was a more humane way to quickly punish sailors at sea than flogging, which the U.S. Navy discontinued in 1862.

The United States continued using bread and water confinement because it was a more humane way to quickly punish sailors at sea than flogging, which the U.S. Navy discontinued in 1862.

Cuba. In Europe, the Berlin Wall was constructed following decades-long Soviet blockades leading to the activation of more than 150,000 US guardsmen and reservists together with Operation Stair Step, the largest jet deployment in history. Then in October 1962, provoked by ongoing US efforts against Cuba (Operation Mongoose), the world held its breath as nuclear war was wagered during the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Growing complexity on the world stage, in combination with civil rights reformation, made timely and accurate intelligence at the highest levels of government indispensable. So, in 1962 President Kennedy authorized the formation of an elite special-ops unit, liberated from red tape and able to deploy at a moment's notice. A unit that did not need to wait for orders to mobilize and arrived armed with state-of-the-art equipment to carry out their mission. Christened DASPO, Department of the Army Special Photographic Office, the corps was a Special Forces unit of sorts but comprised of combat photographers.

Cuba. In Europe, the Berlin Wall was constructed following decades-long Soviet blockades leading to the activation of more than 150,000 US guardsmen and reservists together with Operation Stair Step, the largest jet deployment in history. Then in October 1962, provoked by ongoing US efforts against Cuba (Operation Mongoose), the world held its breath as nuclear war was wagered during the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Growing complexity on the world stage, in combination with civil rights reformation, made timely and accurate intelligence at the highest levels of government indispensable. So, in 1962 President Kennedy authorized the formation of an elite special-ops unit, liberated from red tape and able to deploy at a moment's notice. A unit that did not need to wait for orders to mobilize and arrived armed with state-of-the-art equipment to carry out their mission. Christened DASPO, Department of the Army Special Photographic Office, the corps was a Special Forces unit of sorts but comprised of combat photographers. The unit was populated by cherry-picking the best of the best from the staff at the Army Pictorial Center and students from the Army Signal School at Fort Monmouth, while staff began to fill the ranks of command positions with sound specialists, motion picture cameramen, and still photographers. Meanwhile, Jones (now a Lieutenant Colonel) and his staff kept a vigil for draftees with backgrounds that matched the unit's mission. Comprised of lifers and green recruits, enlistees, and draftees, it would seem the only thing DASPO personnel had in common was that they had little in common, as few men followed the same path to the unit. When asked how he was selected for DASPO, retired Hollywood cameraman Stewart Barbee, who served as a DASPO motion picture cameraman from 1969-70, swears, "I still don't know." On the other hand, veteran photographer Peter "Rupy" Ruplenas had seen combat as a Signal Corps photographer in World War II and the Korean War before volunteering to DASPO in 1966.

The unit was populated by cherry-picking the best of the best from the staff at the Army Pictorial Center and students from the Army Signal School at Fort Monmouth, while staff began to fill the ranks of command positions with sound specialists, motion picture cameramen, and still photographers. Meanwhile, Jones (now a Lieutenant Colonel) and his staff kept a vigil for draftees with backgrounds that matched the unit's mission. Comprised of lifers and green recruits, enlistees, and draftees, it would seem the only thing DASPO personnel had in common was that they had little in common, as few men followed the same path to the unit. When asked how he was selected for DASPO, retired Hollywood cameraman Stewart Barbee, who served as a DASPO motion picture cameraman from 1969-70, swears, "I still don't know." On the other hand, veteran photographer Peter "Rupy" Ruplenas had seen combat as a Signal Corps photographer in World War II and the Korean War before volunteering to DASPO in 1966. Team Charlie operated out of a rented three-story gated house in Saigon, only minutes from the Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Dubbed "The Villa," this compound served as both office and barracks from which two and three-person teams would rotate into the field. DASPO photographers followed combat units into every type of terrain in Vietnam; jungles, Highlands, urban settings, swamps, and rice paddies, … capturing the war from a soldier's view and putting themselves at personal risk, suffering the same hardships. Documenting the action at Khe Sanh, Dak To, the La Drang Valley, and countless other operations, photographers would become part of the unit they were covering, enduring what the unit endured, and staying with it until the mission ended or they ran out of film. In one case, Spc. 5 Theodore "Ted" Acheson arrived in Vietnam in February 1968, just days after the Tet Offensive began, and was wounded during a firefight near the city of Hue. Later, during a firefight near La Chu, Acheson filmed a squad of Soldiers destroying a series of enemy bunkers, again exposing himself to hostile fire and shooting one of the only films documenting actions that resulted in a soldier receiving the Medal of Honor, Spc. 4 Robert Patterson. "The film also shows other acts of valor that resulted in two Silver Stars and five Bronze Star medals," Acheson noted.

Team Charlie operated out of a rented three-story gated house in Saigon, only minutes from the Tan Son Nhut Airbase. Dubbed "The Villa," this compound served as both office and barracks from which two and three-person teams would rotate into the field. DASPO photographers followed combat units into every type of terrain in Vietnam; jungles, Highlands, urban settings, swamps, and rice paddies, … capturing the war from a soldier's view and putting themselves at personal risk, suffering the same hardships. Documenting the action at Khe Sanh, Dak To, the La Drang Valley, and countless other operations, photographers would become part of the unit they were covering, enduring what the unit endured, and staying with it until the mission ended or they ran out of film. In one case, Spc. 5 Theodore "Ted" Acheson arrived in Vietnam in February 1968, just days after the Tet Offensive began, and was wounded during a firefight near the city of Hue. Later, during a firefight near La Chu, Acheson filmed a squad of Soldiers destroying a series of enemy bunkers, again exposing himself to hostile fire and shooting one of the only films documenting actions that resulted in a soldier receiving the Medal of Honor, Spc. 4 Robert Patterson. "The film also shows other acts of valor that resulted in two Silver Stars and five Bronze Star medals," Acheson noted. The photographs and film captured by DASPO document the Vietnam War and are now historical artifacts of this period. After the war, DASPO members established the DASPO Archive and a scholarship fund at Texas Tech University. The scholarship funds the preservation of images and audio recordings in the names of Kermit H. Yoho and Charles "Rick" F. Rein, DASPO members who were killed in action in Vietnam. Specialist Yoho was killed on February 10, 1966, when he was hit by an exploding grenade only seven days before returning to Hawaii following his last 90-day assignment in Vietnam. Sargent Rein was shot down in November 1968 by hostile enemy action while flying over the Kontum province.

The photographs and film captured by DASPO document the Vietnam War and are now historical artifacts of this period. After the war, DASPO members established the DASPO Archive and a scholarship fund at Texas Tech University. The scholarship funds the preservation of images and audio recordings in the names of Kermit H. Yoho and Charles "Rick" F. Rein, DASPO members who were killed in action in Vietnam. Specialist Yoho was killed on February 10, 1966, when he was hit by an exploding grenade only seven days before returning to Hawaii following his last 90-day assignment in Vietnam. Sargent Rein was shot down in November 1968 by hostile enemy action while flying over the Kontum province. Detachment at Fort Bragg. Today the Army's 55th Combat Camera Company at Fort Meade carries out the mission that began with the formation of DASPO in 1962.

Detachment at Fort Bragg. Today the Army's 55th Combat Camera Company at Fort Meade carries out the mission that began with the formation of DASPO in 1962.

Norton was a high-performing athlete his entire life, excelling at track and field and football, among others. Boxing was no different. While serving as a signals intelligence Marine, he would rack up a 24-2 record, making him one of the best fighters to come out of the Marine Corps.

Norton was a high-performing athlete his entire life, excelling at track and field and football, among others. Boxing was no different. While serving as a signals intelligence Marine, he would rack up a 24-2 record, making him one of the best fighters to come out of the Marine Corps.  Norton, meanwhile, was less flashy but putting in the work all the same. Unless you were drawing thousands of people like Ali and Frazier, boxing didn't always pay well. Norton once quipped that a hot dog would be a gourmet meal for him and his son at this point in his career. But by the time he stepped into the ring with Ali, Norton was the sixth-ranked contender in the world.

Norton, meanwhile, was less flashy but putting in the work all the same. Unless you were drawing thousands of people like Ali and Frazier, boxing didn't always pay well. Norton once quipped that a hot dog would be a gourmet meal for him and his son at this point in his career. But by the time he stepped into the ring with Ali, Norton was the sixth-ranked contender in the world.  On March 31, 1973, Ken Norton returned to San Diego, where he'd first learned to box, to fight "The Greatest," Muhammad Ali. No one expected Norton to win the fight at the San Diego Sports Arena that night, and Ali was favored at 1-5 odds. Norton was about to turn into a boxing legend in his own right.

On March 31, 1973, Ken Norton returned to San Diego, where he'd first learned to box, to fight "The Greatest," Muhammad Ali. No one expected Norton to win the fight at the San Diego Sports Arena that night, and Ali was favored at 1-5 odds. Norton was about to turn into a boxing legend in his own right. Norton would fight Ali a total of three times, with the third coming at Yankee Stadium in New York in 1976. The second fight was a close split decision the judges handed to Ali. The third match was also a close call given to Ali, but it was the one that most people watching (and Ali himself) believed that Norton actually won.

Norton would fight Ali a total of three times, with the third coming at Yankee Stadium in New York in 1976. The second fight was a close split decision the judges handed to Ali. The third match was also a close call given to Ali, but it was the one that most people watching (and Ali himself) believed that Norton actually won.

The names Pete Mitchell and Nick Bradshaw might mean very little to most, but when these two are called by their aviator call signs "Maverick" and "Goose," that all changes even though they're the same characters.

The names Pete Mitchell and Nick Bradshaw might mean very little to most, but when these two are called by their aviator call signs "Maverick" and "Goose," that all changes even though they're the same characters.  By World War II, the use of call signs grew in popularity. Pilots and other aviation officers had names based on their appearance, personality, background, or some pop-culture reference. One of the best examples from this era is Marine Corps Col.Gregory Boyington, whose call sign references his age compared to the rest of his pilots.

By World War II, the use of call signs grew in popularity. Pilots and other aviation officers had names based on their appearance, personality, background, or some pop-culture reference. One of the best examples from this era is Marine Corps Col.Gregory Boyington, whose call sign references his age compared to the rest of his pilots. stories are told, and ideas are tossed around. Within about a year or so, the worst possible outcome happens when their co-workers take a vote on what to call the new guy or gal.

stories are told, and ideas are tossed around. Within about a year or so, the worst possible outcome happens when their co-workers take a vote on what to call the new guy or gal.

Every veteran has a unique and interesting story to tell. Many of us are plucked out of our lives in the United States and sent to join our chosen branch of service, where we often travel around the country and around the world, engaging our senses in a series of new experiences. Air Force veteran Buck Cole is one of us.

Every veteran has a unique and interesting story to tell. Many of us are plucked out of our lives in the United States and sent to join our chosen branch of service, where we often travel around the country and around the world, engaging our senses in a series of new experiences. Air Force veteran Buck Cole is one of us.  His stories begin in Waco, Texas, where he grew up in the 1960s and decided to join the U.S. Air Force during the height of the Vietnam War. Younger veterans will relish his descriptions of what it was like to make the transit to basic training at the time.

His stories begin in Waco, Texas, where he grew up in the 1960s and decided to join the U.S. Air Force during the height of the Vietnam War. Younger veterans will relish his descriptions of what it was like to make the transit to basic training at the time.

Ericson had been playing the bugle since age 11 when he joined the Drum and Bugle Corps of Quincy's American Legion Post 37. This fortuitous association placed him among young men of the nation's best-drilled Corps. In 1946, the Quincy Corps, with young Ericson on the bugle, won the national championship in San Francisco.

Ericson had been playing the bugle since age 11 when he joined the Drum and Bugle Corps of Quincy's American Legion Post 37. This fortuitous association placed him among young men of the nation's best-drilled Corps. In 1946, the Quincy Corps, with young Ericson on the bugle, won the national championship in San Francisco. Robert "Bob" Ericson was born on August 22, 1930, and except for three years in the USMC, he lived in Quincy his entire life. His father was a World War I veteran who later became a postal worker. In 1948, Ericson married Gladys Holtschlag and, after his discharge on January 4, 1954, accepted a job offer from his father-in-law, the owner of Holtschlag Florist. For the first eight years of his 35-year career, he worked in the greenhouse as a grower, learning this trade on the job and by using the G.I. Bill for specialized horticultural training. He then became a floral designer, and in 1969 the National FTD named him Designer of the Year.

Robert "Bob" Ericson was born on August 22, 1930, and except for three years in the USMC, he lived in Quincy his entire life. His father was a World War I veteran who later became a postal worker. In 1948, Ericson married Gladys Holtschlag and, after his discharge on January 4, 1954, accepted a job offer from his father-in-law, the owner of Holtschlag Florist. For the first eight years of his 35-year career, he worked in the greenhouse as a grower, learning this trade on the job and by using the G.I. Bill for specialized horticultural training. He then became a floral designer, and in 1969 the National FTD named him Designer of the Year.