Other Comments:

Initially sworn into the USCG - OSS section: Operational Swimmer Group I trained in Coronado and the Bahamas and was later assigned and integrated into the U.S. Navy Underwater Demolition Team 10 in the Pacific Theater July 1944 - July 1945:

The Case of the Reluctant Actor

|

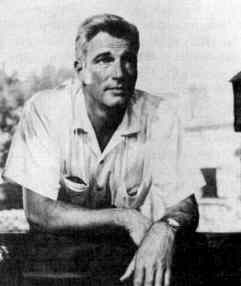

| Bill Hopper, the reluctant actor.Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Science |

Where Raymond Burr encountered humiliation and tragedy in fulfilling his lifelong ambition to be an actor, Bill Hopper, television's Paul Drake, had an acting career handed to him on a silver platter. The problem was, he didn't want it.

"I became an actor," he once said, "because it seemed the easiest thing to do and because it was expected of me. But it stunk."

Most fans probably don't realize that Bill Hopper was actually the son of Hedda Hopper, the Hollywood actress turned columnist. It was a connection Bill Hopper consciously tried to downplay during most of his acting career. Born William DeWolf Hopper, Jr., in 1915, Bill was the son of elderly DeWolf Hopper, the musical comedy stage and screen veteran whose most famous role was probably his deadball version of "Casey at the Bat" in the 1916 film. "Wolfie," as the old man was called, had a penchant for young wives Hedda was his fifth. When the marriage came apart in 1922, Bill, then seven years old, stayed with his mother. Their bonding would grow into one of mutual love but extreme annoyance as the youngster got older. Hedda was his fifth. When the marriage came apart in 1922, Bill, then seven years old, stayed with his mother. Their bonding would grow into one of mutual love but extreme annoyance as the youngster got older.

Hedda "the Hat" (born Elda Furry in 1890), came to Hollywood first as an actress, appearing in more than forty films including everything from Sinners in Silk (1924) toAdam and Evil (1927). She became a syndicated newspaper columnist around 1936 and did radio spots also. It was the beginning of a career that would make her one of the most influential voices in Hollywood quite possibly the most influential from the late 1930s through the 1950s. (Columnist Louella Parsons ran a close second.) These were the days of the Hollywood studios' "star system," and Hedda had access to a lot of inside information. Therefore, when Hedda spoke, Tinseltown listened. Her columns were filled with gossip, fact, and rumor quite possibly the most influential from the late 1930s through the 1950s. (Columnist Louella Parsons ran a close second.) These were the days of the Hollywood studios' "star system," and Hedda had access to a lot of inside information. Therefore, when Hedda spoke, Tinseltown listened. Her columns were filled with gossip, fact, and rumor one word from Hedda could make or break a career. Many producers, directors, actors, and starlets took notice of her "suggestions" and adjusted their star paths accordingly. As TV Guide put it, her words were akin to "a general's orders to a private." one word from Hedda could make or break a career. Many producers, directors, actors, and starlets took notice of her "suggestions" and adjusted their star paths accordingly. As TV Guide put it, her words were akin to "a general's orders to a private."

It's no surprise that a woman as powerful as Hedda liked getting her own way, and most of the time she did. The exception was with her son, Bill. The young Hopper just didn't have the right chemistry to fit into his mother's fast-paced life. More shy than rebellious, he apparently spent most of his adolescence looking for ways not to get involved in the Hollywood kissy-kissy scene. He deliberately made friends outside of movieland's strata and harbored an open dislike for the never-ending celebrity parties that were Hedda's lifeblood.

"I didn't dislike movie people," Bill once told TV Guide. "But they were nothing special to me. I'd been around them all my life. My mother's the kind who could say 'Howdeedo' to the king of England and feel perfectly at home. But I couldn't."

Trouble was, Hedda demanded that her son become a success in her world of moving pictures. When he resisted, Hopper's life became a perpetual game of trying to find oneself in spite of mommy's help.

"What Hedda wants, Hedda gets," is how a friend put it. "She wanted Bill to be part of her way of life. When Bill wouldn't cooperate, it drove her nuts."

Unwilling though he was, Hopper became a very visible, well-publicized momma's boy during the 1930s. (He rarely saw his father, a man of fifty-seven when Bill was born. Wolfie died at age seventy-seven in 1935.) Hedda bought her son everything from his toys to his suits. She sent him to the best schools. But not even motherhood could slow down an ambitious person like Hedda. Her son suffered as a result.

From all reports, however, Hedda was genuinely (some say, surprisingly) touched when discussing her son. She was aware of how hard it was on him being the offspring of Hollywood's most famous buttinsky. "I love my son," she said once in a moment of candor, "but he is so much better when I am not around."

As he grew older, young Hopper became quite capable of making his own decisions. Yet even then he constantly had to fend off his mother's overdeveloped concern, which frequently got out of line. Ironically, in the light of his subsequent TV role, she told him that if he didn't want to be an actor, she'd make him a lawyer. Bill reluctantly opted for the screen, but didn't bust down any doors in doing so.

So Hedda did it for him. In 1936, she arranged for him to play summer stock in Maine. Later on, he apparently impressed someone playing a minor role in Romeo and Juliet,because he was signed to his first movie contract soon afterward.

Hollywood, however, was just barely 'whelmed. Going by the stage name of DeWolf Hopper, Jr., he played his first screen role in 1937. Although he did appear in classics such as Knute Rockne All American (1940), and The Maltese Falcon (1941), he also showed up in losers like Women Are Like That (1937), Daredevil Drivers (1938), andNancy Drew and the Hidden Treasure* (1939). His biggest accomplishment during this period appears to have been as an answer to the Hollywood trivia question: What actor played in the B movie Public Wedding with a then unknown actress who went on to divorce a future president of the United States? (Answer: DeWolf Hopper, Jr. The actress? Jane Wyman.) All American (1940), and The Maltese Falcon (1941), he also showed up in losers like Women Are Like That (1937), Daredevil Drivers (1938), andNancy Drew and the Hidden Treasure* (1939). His biggest accomplishment during this period appears to have been as an answer to the Hollywood trivia question: What actor played in the B movie Public Wedding with a then unknown actress who went on to divorce a future president of the United States? (Answer: DeWolf Hopper, Jr. The actress? Jane Wyman.)

This appearance notwithstanding, most of his roles continued to be small. Which is how Hopper preferred them. He was still living at home, so he didn't need the money. It was about this time that Hedda moved from screen star to screen columnist. Even more than before, Bill Hopper felt trapped in the large shadow of Hedda's famous hats.

"I was always conscious that no matter what I did, someone was thinking Hedda had arranged it," Hopper once said. "Half the time she had, too. Producers began asking my agent, 'But how much trouble will Hedda give me?'"

For instance, there was the time he was negotiating a contract at Fox on his own. Hedda found out and called the studio. But the producer turned out to be a rare item; he stood up to her. Goodbye contract at Fox.,

It took a production as big as World War 11 to give Hopper a chance to get away from it all. In 1942, he joined the Coast Guard. He worked in underwater demolition and was good at it maybe too good. His frogman team was originally chosen to lead the way for the possible invasion of Tokyo, a suicidal mission if there ever was one. However, Hopper was injured in the Philippines and returned home from the war in 1945 a hero. His mother was apparently more concerned than proud of her son's bravery, but for Bill Hopper it had been days of glory maybe too good. His frogman team was originally chosen to lead the way for the possible invasion of Tokyo, a suicidal mission if there ever was one. However, Hopper was injured in the Philippines and returned home from the war in 1945 a hero. His mother was apparently more concerned than proud of her son's bravery, but for Bill Hopper it had been days of glory perhaps more glory than he would ever find on the screen. perhaps more glory than he would ever find on the screen.

That question wouldn't be answered for almost a decade. After the service, Hopper dropped out of Hollywood life to sell cars. He was the first to admit that he wasn't good at it. In addition, his boss wasn't above using Bill and his famous mother as steppingstones to some lucrative Hollywood connections. And when things got tough, Hedda was right there as usual, offering to buy Bill his own business. Yet Hopper stuck with it for eight years, supporting his wife, Jane, whom he had married in 1940, and his young daughter, Joan, who was born in 1947. (This marriage would go awry, at least temporarily, in 1962.) to sell cars. He was the first to admit that he wasn't good at it. In addition, his boss wasn't above using Bill and his famous mother as steppingstones to some lucrative Hollywood connections. And when things got tough, Hedda was right there as usual, offering to buy Bill his own business. Yet Hopper stuck with it for eight years, supporting his wife, Jane, whom he had married in 1940, and his young daughter, Joan, who was born in 1947. (This marriage would go awry, at least temporarily, in 1962.)

Hedda was to be proud of her son yet. In 1953, Bill Hopper was coaxed out of the car business and back into show business to pick up where he had left off before the war. William Wellman cast him in The High and the Mighty as the cowboy playing across from Jan Sterling. But he still felt suspicious that momma was pulling strings behind the scenes. At the time, Wellman claimed he didn't know Hopper was Hedda's son. Luckily, Wellman wasn't under oath at the time. Son Hopper knew better: "I was very doubtful. When it appeared Wellman was serious, I asked him if he knew whose son I was. He ignored me. I was so lousy, so nervous, I didn't even know where the camera was. But somehow Billy got me through. Afterward, I thanked him. He said, 'Thank me, my foot. After this, you're going to be in every picture I make.' I didn't believe him."

Shortly afterward, Hopper was cast in his first live TV show, a Lux Video presentation with Claire Trevor called "No Sad Songs for Me."

"I was so scared I canceled," Hopper remembered. "I swore I'd never act again as long as I lived. Then I thought, what the heck, they can't shoot me, and walked on the set. Something happened then. It was as if someone had surgically removed the nerves."

By 1955, Hopper had become more comfortable on the screen. He showed up with dozens of other actors with dozens of other actors to test for the role of TV's Perry Mason. But when Burr got Mason, Hopper got Paul Drake. Years after their roles were cast, Hopper said: "He [Burr] was everybody's idea of what Perry really was like, while I was some guy with prematurely gray hair. to test for the role of TV's Perry Mason. But when Burr got Mason, Hopper got Paul Drake. Years after their roles were cast, Hopper said: "He [Burr] was everybody's idea of what Perry really was like, while I was some guy with prematurely gray hair.

"I don't think I could have handled Mason. I'm just not that dedicated."

But Hopper was finally working steadily in the industry and undoubtedly Hedda felt she had won. And she let the world know about it. Never one to contain her gift of gab, Hedda always positively blubbered over her son's exploits in her columns. Finally, Hopper put his foot down. About the time he joined the cast of "Perry Mason," he ordered her never to use his name in her column again.

As Paul Drake, William Hopper was called on to be the most versatile of the principals in the "Perry Mason" cast. Whereas Burr never wavered for a moment from the granite-willed Perry Mason, nor Hale from the sexy-solid Della Street, Hopper had many parts to play. He was not only the careful investigator, the duke-it-out tough guy, the ladies' man, and the hipster, but also the fall guy, the strikeout artist, the "eating machine," and "the big kid." Hopper's Drake alone provided the comic relief for the show. And, despite being a rather late bloomer to the acting field, he played all the parts surprisingly well and believably. His appearances made fair shows good, good shows better.

As head of the Drake Detective Agency (phone number: CRestview 9-7441), Paul was always available especially when Perry Mason called. He was the only one to have access to the private side door to Perry's office. If he was entering through the front door, he'd deliver a "Hello, beautiful!" to Della. especially when Perry Mason called. He was the only one to have access to the private side door to Perry's office. If he was entering through the front door, he'd deliver a "Hello, beautiful!" to Della.

He was an important third of a great team. Perry was the brains, Paul the brawn, and Della had the legs. Like a one-man U.S. cavalry, Paul's forte was to arrive in court at the last possible moment and stage whisper to Perry that he'd found the crucial evidence they'd been looking for. And more so than the lawyer, Paul was street-smart. He could play hardball with the worst of them the petty thieves, the ex-cons, the rugged dockworkers. If friendly persuasion or a friendly bribe failed, he'd just punch 'em out. No problem, just part of the well-paid job. Paul Drake was a study in contrasts, though. He was a tough guy who had a weakness for chocolate ice cream. He was a sturdy, handsome man who never sat, only slouched, even in court. He was a braggart, but not arrogant. He was an avid ladies' man the petty thieves, the ex-cons, the rugged dockworkers. If friendly persuasion or a friendly bribe failed, he'd just punch 'em out. No problem, just part of the well-paid job. Paul Drake was a study in contrasts, though. He was a tough guy who had a weakness for chocolate ice cream. He was a sturdy, handsome man who never sat, only slouched, even in court. He was a braggart, but not arrogant. He was an avid ladies' man 100 percent wolf 100 percent wolf but with as many rejections as conquests. And although usually he drove a cool-daddy ragtop Thunderbird (license plate number LTZ-413), he apparently couldn't resist wearing white socks under his dapper, 1950s wardrobe. but with as many rejections as conquests. And although usually he drove a cool-daddy ragtop Thunderbird (license plate number LTZ-413), he apparently couldn't resist wearing white socks under his dapper, 1950s wardrobe.

Like Perry and Della, Paul just appeared on the scene, a man with no past. He was the private dick who "got paid to be curious." He also got paid for doing Perry's dirty work. Although unwavering in his trust for the good lawyer's judgment, Paul wasn't always sure what he was getting himself into. When he hid a fugitive client in a hotel per Perry's orders ("The Case of the Difficult Detour"), and asked the lawyer, "Am I breaking the law again?" it was with good reason. He and Perry were constantly entering houses and apartments illegally, searching for evidence that would be thrown out in a millisecond in today's courts. And, on at least one occasion (see "The Case of the Angry Mourner"), one of his confederates impersonated a police officer to get the goods on a hostile witness.

So, it comes as no surprise that Paul was also arrested more than once, as in "The Case of the Poison Pen-Pal." Hired by one Peter Gregson to plug an insider's leak that could ruin Gregson's business, Paul cased a house belonging to a woman named Karen Ross. He got hauled in by the cops for his efforts, accused of breaking and entering. But, no sooner was he released (the lady dropped the charges) than he was right back in hot water again. He was also subpoenaed many times, "The Case of the Bartered Bikini" being just one example; he was summoned to court to testify for the prosecution.

Drake never shied away from the tough cases, though. He tackled the Mob during a trip to Boston with Perry and Della in "The Case of the Stand-in Sister." Tracking down an underworld kingpin named "Big Steve," Paul put him on the business end of a revolver and pumped him for the info Perry needed for the case. Then he put the gangster where he belonged: behind bars.

He was a man of many talents a karate expert, as he proved in "The Case of the Terrified Typist," and he played a mean game of cards, one time shrewdly bilking a professional gambler out of some IOUs that belonged to one of Perry's clients. And he was a thorough gumshoe. His operatives were everywhere. In "The Case of the Ill-fated Faker," his dogged persistence paid off when he went looking for a suspected murderer named Stan Piper, only to find that Stan was the killed, not the killer, and that the real murderer was alive and hiding out until he was pronounced legally dead. And in "The Case of the Pint-sized Client," it was Paul who knew right where to find "songbird" Eddie Merlin, a local stool pigeon who was sitting on some valuable information. a karate expert, as he proved in "The Case of the Terrified Typist," and he played a mean game of cards, one time shrewdly bilking a professional gambler out of some IOUs that belonged to one of Perry's clients. And he was a thorough gumshoe. His operatives were everywhere. In "The Case of the Ill-fated Faker," his dogged persistence paid off when he went looking for a suspected murderer named Stan Piper, only to find that Stan was the killed, not the killer, and that the real murderer was alive and hiding out until he was pronounced legally dead. And in "The Case of the Pint-sized Client," it was Paul who knew right where to find "songbird" Eddie Merlin, a local stool pigeon who was sitting on some valuable information.

He did like to brag. When asked by Perry about the qualifications of one of his operatives, Paul boasted, "He's a good investigator. I trained him myself." Or, once "The Case of the Wintry Wife" was solved, he had the chutzpah to say: "It was all pretty obvious anyway." This was after Perry had figured out all the tough parts. ("It's all pretty obvious now!" an astonished Della reminded him.)

But he'd do anything to help Perry clear a client. In "The Case of the Angry Astronaut," Paul's investigation of why a spaceman was acting spacey got turned upside down. Literally. When Paul took a ride in a simulated space capsule, it felt too much like the real thing. He came out of the test looking for his stomach.

Paul fancied himself a connoisseur of fine food and not so fine food. Truth is, he'd eat almost anything, especially if he was spending Perry's money. As Della put it, "This is the world's greatest detective when it comes to finding food." Once, she cornered him after receiving a bill from the Drake Detective Agency. "I can never understand how you are able to consume so much food, especially when you are on an expense account." Paul's reply? "I'm a growing boy." In "The Case of the Purple Woman," when Lieutenant Tragg confronted Perry, Paul, and Della in a restaurant with disturbing news about a case, it was so bad that Perry and Della immediately lost their appetites. But not Paul. He dug in as usual. How could he eat at a time like this? Because he was still "a growing boy." and not so fine food. Truth is, he'd eat almost anything, especially if he was spending Perry's money. As Della put it, "This is the world's greatest detective when it comes to finding food." Once, she cornered him after receiving a bill from the Drake Detective Agency. "I can never understand how you are able to consume so much food, especially when you are on an expense account." Paul's reply? "I'm a growing boy." In "The Case of the Purple Woman," when Lieutenant Tragg confronted Perry, Paul, and Della in a restaurant with disturbing news about a case, it was so bad that Perry and Della immediately lost their appetites. But not Paul. He dug in as usual. How could he eat at a time like this? Because he was still "a growing boy."

Della and Perry got their revenge in "The Case of the Negligent Nymph." The threesome were eating at a Mexican restaurant. Although they warned him about the tamales, Paul hung tough, convinced he could handle his food like his women hot. Big mistake. Paul felt as if he'd just eaten a five-alarm fire. The next time the trio stepped out to the same little hideaway, Paul decided to play it safe and order the ham and eggs. Della and Perry bit their lips as they watched Paul* pour what he thought was catsup all over his food. It turned out to be hot (no, very hot) sauce. The big guy got burned a second time. hot. Big mistake. Paul felt as if he'd just eaten a five-alarm fire. The next time the trio stepped out to the same little hideaway, Paul decided to play it safe and order the ham and eggs. Della and Perry bit their lips as they watched Paul* pour what he thought was catsup all over his food. It turned out to be hot (no, very hot) sauce. The big guy got burned a second time.

Still, Paul was one for creature comforts female creatures mostly. But just like Perry and Della, his sex life was also a bit mysterious. female creatures mostly. But just like Perry and Della, his sex life was also a bit mysterious.

On the surface, one would think that Paul was a real hustler, kind of a gentleman masher. Witness "The Case of the Curious Bride," when he could barely contain himself after going backstage at a dance troupe rehearsal to question some leggy witnesses. Or "The Case of the Ancient Romeo," when he smoothly sweet-talked a lady bank teller into giving him the scoop on some missing money. In "The Case of the Impetuous Imp," authoress Diana Carter was so enamored of him, she saw fit to dedicate her adventure novel to Paul. The title was The Amorous Adventures of Paul Lake, Private Eye.

Paul's eyes would pop out over the opposite sex with clockwork regularity. During "The Case of the Calendar Girl," he and Della were studying a photo of a bikini-clad client and discussing her narrow escape from thugs.

"The way I see it," Della said, "Dawn Manning got by, by the skin of her teeth."

"The way I see it," Paul said, "there's more skin than teeth."

In "The Case of the Carefree Coronary" we have evidence that when Paul scored, he scored big. Trying to solve a fraud case, Perry called Paul in on emergency duty. Paul, however, was working on a hot case of his own: "This better be good," he told Perry, "because I just tore myself away from a very delectable divorcée."

But sometimes he blundered, stumbled, and fell. In "The Case of the Candy Queen," he blew a chance to romance Perry's beautiful client, Claire Armstrong, owner of a large and lucrative candy empire. Claire was about to leave for a long trip and Perry and Della were seeing her off when Paul showed up with a farewell gift, something he thought she just couldn't get enough of. yet another box of candy.

When Perry won "The Case of the Shapely Shadow," it gave Paul the opportunity he needed to invite the sexy client, Janice Wainwright, out to dinner. After all, the poor girl had been shut in and just came through a terrible ordeal after being accused of murder. But alas, Paul struck out again. Any detective worth his wolf whistle should know a dish like Janice would already have a date.

Was it that he was forever looking for the right girl? Maybe. We find a clue in "The Case of the Howling Dog." Perry asked Paul if he could find a good-looking brunette to impersonate a client. The lawyer went to great lengths to describe the kind of actress he wanted:

Perry: "Now, do you think you can find one just like that?"

Paul: "I've been looking for one for years."

We must assume that Paul eventually found her and got hitched. His son, Paul Drake, Jr., would show up in 1985 to help Perry clear Della of a murder frame-up in "Perry Mason Returns," and become part of Perry's new team.

Probably Paul's most challenging case was the one in which he found himself the accused. In "The Case of Paul Drake's Dilemma," the detective was framed for committing a homicide. Good thing he knew a good lawyer. The scenario is familiar one of a number of "amnesia murders" that our heroes were always running into. Paul found out that one Frank Thatcher was guilty of a hit-and-run accident that hurt innocent people. The detective confronted him and pressured Thatcher for a confession. The creep resisted, so Paul had no choice but to slug it out with him. It was a great fight one of a number of "amnesia murders" that our heroes were always running into. Paul found out that one Frank Thatcher was guilty of a hit-and-run accident that hurt innocent people. The detective confronted him and pressured Thatcher for a confession. The creep resisted, so Paul had no choice but to slug it out with him. It was a great fight that is, until Paul hit his head and was knocked out cold. Once he came to, he found he was at the scene of a killing and had no idea what had happened. Although Hamilton Burger didn't want to prosecute someone he knew so well, Tragg put the pressure on. The evidence against Paul looked bad. But Perry went to work and, in the end, the detective was cleared. The lawyer maintained that he never had any doubts about Paul's innocence-but then jokingly added: "Wait till you see my bill." that is, until Paul hit his head and was knocked out cold. Once he came to, he found he was at the scene of a killing and had no idea what had happened. Although Hamilton Burger didn't want to prosecute someone he knew so well, Tragg put the pressure on. The evidence against Paul looked bad. But Perry went to work and, in the end, the detective was cleared. The lawyer maintained that he never had any doubts about Paul's innocence-but then jokingly added: "Wait till you see my bill."

Maybe the toughest part Paul had to play was that of a friend to Perry Mason, a man who, by definition, had no close friends.

There was a revealing moment in "The Case of the Sausalito Sunrise." Perry and Paul were waiting to make a late-night rendezvous with a mysterious client. Perry was somewhat frustrated, as this client was not cooperating. In an unguarded moment, he unloaded his problems on his friend. "I sometimes wonder about this profession," Perry said. "Clients pay you for your advice, then stubbornly refuse to take it."

Paul replied: "Shouldn't you be grateful? After all, if everyone acted logically and sensibly, who would need lawyers?"

Or detectives for that matter ...

Just as Raymond Burr will always be Perry Mason, Bill Hopper will always be Paul Drake. He defined the role. In doing so, Hopper came into his own in the same world he had feared, resented, and avoided. His friendships on the Mason show were a source of joy and emotional support. He shared a dressing room with Bill Talman for years and both men boasted they never had a disagreement in all that time. Despite all the togetherness they experienced in one of the hardest-working TV companies ever, Hopper could not resist joining Barbara Hale and Talman in playing summer stock comedies while the Mason show filming was on hiatus.

He was comfortable and popular off the set, too. Robert Mitchum was a chum, as was the pseudo-prince-turned-restaurateur Mike Romanoff. With the outstanding success of the series, Bill Hopper could finally be sure that mom could not take the credit for all his efforts and achievements. Other TV series offers came his way, but he turned them down. After "Perry Mason" went off the air, he played a few more roles here and there. His last was in Myra Breckenridge, which was unleashed upon the public in 1970. Always he was content to play the good-natured neighbor, sidekick, or slob rather than the dashing hero, the self-described "pleasant fellow whom you like having around the family living room."

"Oh, I've learned some tricks," he told a TV Guide interviewer once. "Like how to say, 'Perry, which way did they go?' several hundred different ways, and maybe charm a few modest birds off a few trees while doing it. And maybe even pop would be proud. But essentially I'm a nonthrobbing actor. I'm sorry, pop, but that's what I am."

In many ways, like his famous character, he arrived on the scene at the last possible moment. Saved from a life of avoiding momma and selling Chevys, he slipped in by that side door. Hearts didn't melt, Oscar never came knocking. But that was all right.

"I am not Gable," he told his mother once. "Never was. Never will be."

Bill Hopper died on March 6, 1970, of pneumonia, the same affliction that had taken his mother, Hedda, in 1966.

Source: http://www.perrymasontvshowbook.com/

|